There’s no such thing as a bad Olive. Us fly tiers being overly fond of the color and have two dozen shades isn’t half enough. While puzzling my way through the RIT Forest Green – Tan – makes – Olive Conundrum, I’d figures out that it was the dye temperature I’d failed to get hot enough, and only the tan had activated.

Now I was admiring another Olive project, a lot bigger – and I was relieved it wasn’t the unknowns of a balky dye I’d be fighting. I could reproduce the desired color in a single pass through the dye bath, and the target material was fur which is much more friendly than moisture repelling duck feathers.

This time the wrinkle is the material isn’t white, which adds a bit of preplanning when converting one of Mother Nature’s colors into something else.

I’d describe the starting color as a warm tan to a warm light brown, and the qualities of its existing color needed to be factored into our conversion to make it a warm medium Olive.

Olive is Green, Yellow, and a bit of dark Gray or Black. The original color isn’t white – so I’d have to count some of it as the dark component of Olive, and it’s a warm color – so it’ll count as yellow as well.

(From past posts, remember adding green cools the olive, adding yellow warms it, and adding more black – darkens it.)

If we took the same dye formula used on white materials, and we didn’t watch the color closely, merely exposing the material to the bath for the same length of time, we’d wind up with Olive both darker and warmer than our target color. So we’ll remove some of the yellow and some of the black in the dye mixture to compensate.

If medium Olive is 45% Green, 45% Yellow, and 10% Black – I’d compensate with dye bath comprised of 65% Green, 25% Yellow, and 5% black.

As my starting dye is not a bright green (like Kelly Green), rather it’s a Forest Green, there’ll be no need to add any black, so the final mix will be 75% Forest Green and 25% Golden Yellow (using RIT colors).

As my starting dye is not a bright green (like Kelly Green), rather it’s a Forest Green, there’ll be no need to add any black, so the final mix will be 75% Forest Green and 25% Golden Yellow (using RIT colors).

At right shows the initial rinse, most of the water bleeding off is cold Green which is expected.

Getting your Monies Worth

A single box of RIT will dye a pound of material, and simple tasks like chicken necks or a Hare’s mask will have you pouring most of your money into the sink. A couple ounces of teal feathers or saddle hackle doesn’t even scratch the coloring potential of the full RIT package, and having open dye packages laying around your garage is a known hazard. It’ll sift out of the box or get dropped onto the garage floor in dry form, and the next time the car is washed you’ll track it into the house.

As a fly tyer in the tertiary grip of the obsession, whose materials are purchased by the pound, dyeing represents a way of breathing new life into chewed up material, or making a lifetime supply of questionable colors less so.

I’ll dye the target material and take advantage of the remaining color in the pot to dye other feathers or picked-over Whiting capes – those whose #14, #16, and #18 hackles have already been removed. I’ll use the butt end of the capes for streamers or big dry flies like Green Drakes or Golden Stones.

Having a complimentary shade of Partridge, Guinea Fowl, or that gifted Pheasant your neighbor blew daylight through – lends an extra hide or skin new life, and recoups some of the money you might have paid.

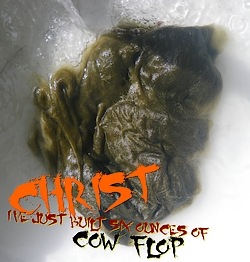

Back to Cow Flop Olive

As I’m already admiring a half pound of cow flop Olive on my carpet, I ran some teal through the dye bath, then followed that with a couple of well chewed Grizzly capes.

Those complimentary colors and dissimilar materials means I’ve got the ability to start tying flies that look cohesive due to color alone. Teal and dubbing is the Bird’s Nest, and dubbing and large Grizzly hackles gives me Green Drakes, Olive Marabou Leeches, and Wooly Buggers.

What most interesting in the picture above is the teal and Grizzly capes. The dye bath was custom built to make a tan into a warm olive, now its true color is revealed to be a cold green. It’s validation of our dye mixture, the tan bleeds through the green to make the fur a warm Olive, and the hackle and teal both started as white/black, and the dye bath builds a colder green absent the warming influence of the tan.

It’s working with Mother Nature’s colors – rather than overpowering them with dye.

… and it’s why you see so many deep dark colors in fly shops and so few pastels. Most commercial vendors use the “overpower” method of dyeing which gut-slams the original color into the background, eliminating the shade it can cast on the final product, and yields dark results.

Working in concert with the original color allows you to build some of the most valuable and sought after colors, like Bronze Blue Dun and the entire Dun family.

The unanswered question is “what am I going to do with half a pound of cow flop Olive?” – mating it with 18 miles of Olive tinsel that I inadvertently purchased is no surprise, but it’s actually a new filler I’m testing – the Poor Man’s Aussie Opossum, only cheaper.

Not to worry, I’ll send samples – once I’ve got the other eight colors dyed.

Tags: dyeing fly tying materials, Olive, colorizing fur, bulk fly tying materials, RIT dyes, teal flank, grizzly hackle, picked over neck, cow flop, fly tying obsession

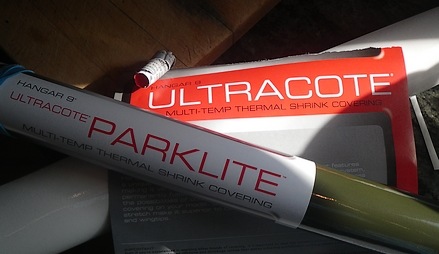

With little help forthcoming from you chaps, I took a chance with another double sawbuck to land Coverite Microlite, another model fabric that doubles as our favorite nymph skin.

With little help forthcoming from you chaps, I took a chance with another double sawbuck to land Coverite Microlite, another model fabric that doubles as our favorite nymph skin.

The simplest way to build a good spectral effect is build the “Chaos” color and simply add it to your base fur in the desired quantity.

The simplest way to build a good spectral effect is build the “Chaos” color and simply add it to your base fur in the desired quantity. At right is the knotted mass that came out of the blender. It mixed the colors slightly, but the bulk of the mixture is still clumped color and undesirable.

At right is the knotted mass that came out of the blender. It mixed the colors slightly, but the bulk of the mixture is still clumped color and undesirable.

I’ve found the material, now I need to find out which brand it is …

I’ve found the material, now I need to find out which brand it is …

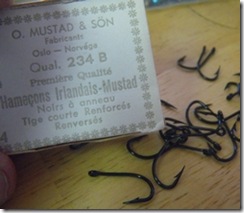

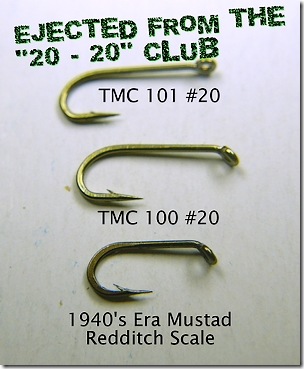

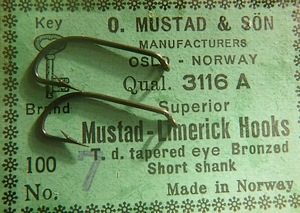

I’m a self confessed collector of hooks and a complete snob. Not that they have to be gilt plated or come from some distant clime, I just need them to be as versatile as screwdrivers and socket wrenches, lots of sizes and similar shapes, but there should be one perfectly suited for the task.

I’m a self confessed collector of hooks and a complete snob. Not that they have to be gilt plated or come from some distant clime, I just need them to be as versatile as screwdrivers and socket wrenches, lots of sizes and similar shapes, but there should be one perfectly suited for the task.

As my starting dye is not a bright green (like Kelly Green), rather it’s a Forest Green, there’ll be no need to add any black, so the final mix will be 75% Forest Green and 25% Golden Yellow (using RIT colors).

As my starting dye is not a bright green (like Kelly Green), rather it’s a Forest Green, there’ll be no need to add any black, so the final mix will be 75% Forest Green and 25% Golden Yellow (using RIT colors).

As today is the much dreaded “Tax Day” I thought I’d interrupt that lethal mix of sulk and stress with a return to the 1950’s – more importantly, a return to 50’s pricing…

As today is the much dreaded “Tax Day” I thought I’d interrupt that lethal mix of sulk and stress with a return to the 1950’s – more importantly, a return to 50’s pricing…

Take a close look at the 3116A, 36712, and 3667 styles, as these are superb hooks.

Take a close look at the 3116A, 36712, and 3667 styles, as these are superb hooks. I’d dutifully

I’d dutifully  them in the pot to test the overnight method. The result is above, a rich dark brown.

them in the pot to test the overnight method. The result is above, a rich dark brown.