I figure my sudden foray into dubbing was like McDonald’s adding salads to an otherwise lard-based menu. How the lights abruptly dimmed and the sudden demand for lettuce left most of the country rediscovering Broccoli for their evening meal.

I figure my sudden foray into dubbing was like McDonald’s adding salads to an otherwise lard-based menu. How the lights abruptly dimmed and the sudden demand for lettuce left most of the country rediscovering Broccoli for their evening meal.

Like the gals and their hair extensions, I was unfazed that I emptied most warehouses of everything furry. I started with the wholesale furriers, worked my way through the local stuff and fur coats on eBay, and when I’d exhausted the obvious sources, I’d make the call to my contact at the SPCA to see what was chilling rapidly …

A couple of months worth of effort turned into the better part of a year’s worth of research, failed automation, test groups and test colors, research on color mixing, dyes … and worse, suddenly needing to find vast amounts of odd animals to include once refined to their final formula.

Failed automation meant having to do it all by hand in the kitchen. Meaning it’s been a lonely year – bread, water, and solitary confinement does that to a person …

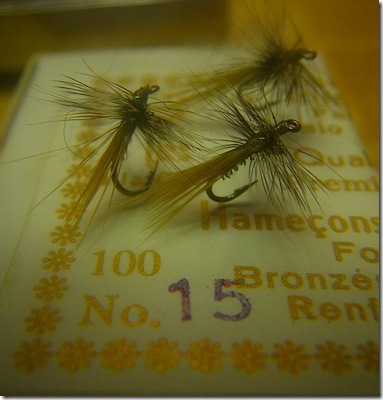

All of this started off simply enough, a general indifference to the dubbing products available in today’s fly shop, most of which featured some sparkly synthetic as its only real quality. Absent from the shelves are the natural dubbings of the past; crafted to make it easy to apply on thread, or coarse so its stubbled profile resembles something comely, or all natural featuring aquatic mammals to make gossamer thin dry fly bodies.

Instead were pushed towards some glittering turd that is about as easy to dub as a Brillo pad, and sparkles like a perfumed tart.

So I brought the manicured styles back; finding in the process that few tiers are left with the skills to refine dubbing to specific tasks, fewer relay the ritual to print to teach others, and most new tiers are content with products the way they are as they’ve not been exposed to others. It’s as if the qualities of fur and the skills to turn them to our advantage are disappearing.

As mentioned in previous posts on dubbing, there are three distinct layers in a crafted dubbing, allowing you to insert distinct qualities as part of each layer’s construction. I’ve likened dubbing construction to a cigar, where the finished product contains binder, filler, and wrapper.

The Wrapper is the coarsest material, often made of animals with well marked guard hair, suitable for adding spike and shag to the finished blend.

The filler is often the coloring agent, made up of semi-coarse or semi-fine materials that comprise the bulk of the dubbing…

… and the binder is the softest component, which is often added in proportion to the filler and wrapper to hold all three layers together in a cohesive bundle.

Somewhere in all of this can be a fourth layer, not always present, that I call “special effects.” Shiny or sparkle, pearlescent or opalescent, some quality that natural materials lack which can be added to liven it with color or a metallic effect.

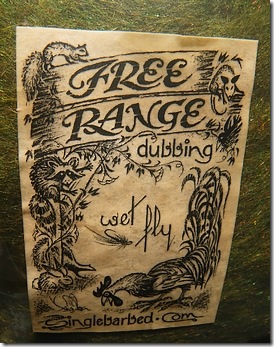

The Free Range Difference

What I’ve constructed is a dubbing designed to assist both beginner and expert tiers by including specific desirable qualities that should belong in any quality nymph dubbing:

Ease of Use: The material isn’t unruly nor possessed of qualities of some Brillo-style gaudy synthetic. The soft binder layer entraps the spiky wrapper and makes dubbing the fur onto the thread easy.

Sized for 8 – 16 hooks: All the fibers present in each color have been sized to best fit your most common sizes of nymphs. That means you won’t be yanking too many overly long fibers out of your dubbing, or off the finished flies, as even the multiple guard hairs used have been chosen for length as well as coloration.

Minimal Shrinkage When Wet: The fibers of the filler layer, which comprise the largest part of the dubbing as well as most of the color, are chosen for their curl, so they will maintain their shape wet or dry, and what proportions leaves your vise will be retained when the fly is soaking wet.

Blended Color versus Monochrome: Each of the colors is the result of between 5 and 11 different materials, each with different shades and tints that add themselves to make the overall coloration. Like Mother Nature, whose insects are never a uniform color, each pinch yields a bit of unique in every fly tied.

Spectral Coloration: The special effects of each are often synthetic spectral color components, containing a range of colors that are sympathetic with the overall blend color.

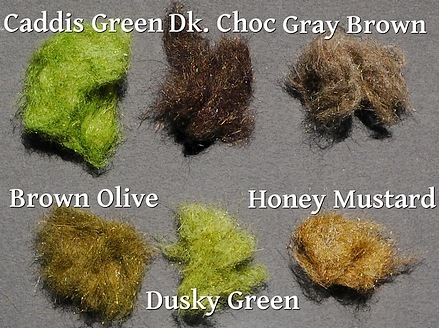

Only Buggy Colors: We chose to concentrate our colors into traditional insect hues leaving the lightly used colors out of the collection. Most fly tiers have a drawer filled with colors that are rarely used, we’d prefer to focus on the “money” colors like olive and brown.

Rather than a single color of Olive, we’ll offer a half dozen olives – as they’re far more useful than coral pink or watermelon. We’ve done the same for brown and gray, and even added effects to make more than a single black.

Food-based Names: Everyone knows that colors named with food references are twice as tasty to fish. We got’em, they don’t – ’nuff said.

Twice as much: Earlier in the research phase of the project I discovered the average dubbing vendor now only gives you 0.91 of a gram with 2 grams of brightly painted cardboard. I’ll give you a couple grams of goodie, and a biodegradable slip of paper instead …

What it isn’t …

It’s not going to leap onto your thread unassisted, nor will it make your fingers less tacky and curb your propensity to grab too much. It’s not some painted harlot made gaudy by too much color. Special effects are nearly invisible to the eye, representing about 2% of the fiber, and until the fur is moved into direct sunlight, only then can you see the refractive elements that make the mix glow and sparkle.

Naturally once someone says, “ … and the trout see …” Everything past that is a leap of faith. Millions of nice fellows have roused from their cups to pound table and insist trout love something or other. This entire collection is my sermon on colors and textures, imbued with everything I hold sacred.

Until I can get some automation in place this is more a labor of love than profit. I managed to incur some fierce loyalties to the end result from many of the folks testing, and with a new season about to debut and them tying to make up for lost time, they’re looking for me to live up to my end of the bargain.

I have 20 colors completed and am planning about 10 additional colors to fill gaps. Most of the Olives and Browns and Grays are completed already, I just need to see what I reach for that isn’t there.

Yes, we’re a bit ahead of our supply lines still, but the season starts next weekend, and I can’t have you feeling naked and resentful. I figure after a couple trips into the season I’ll know exactly what’s missing.

If you would like a sample of the dubbing, drop me a note. I’ll put something in there you’ll like and you can send me a stamped envelope to cover my expenses …

Technorati Tags:

dubbing,

fur blends,

spectral dubbing,

filler,

binder,

wrapper,

special effects,

guard hair,

dyed fur,

mottled color,

fly tying materials

Contrast the above with the hair available in front of its ears, on its forehead and along its snout.

Contrast the above with the hair available in front of its ears, on its forehead and along its snout.

I figure my sudden foray into dubbing was like McDonald’s adding salads to an otherwise lard-based menu. How the lights abruptly dimmed and the sudden demand for lettuce left most of the country rediscovering Broccoli for their evening meal.

I figure my sudden foray into dubbing was like McDonald’s adding salads to an otherwise lard-based menu. How the lights abruptly dimmed and the sudden demand for lettuce left most of the country rediscovering Broccoli for their evening meal.

Invariably someone asks me, “what’s the hardest thing in fly tying?”

Invariably someone asks me, “what’s the hardest thing in fly tying?”

What’s not so smart is most of them are selling under the shop account, and was I the Whiting Hackle Company I might want to be bring a couple of those vendors up short, as I have enough troubles keeping the fly tying market in feathers without some sharp SOB hoarding all the good saddles in the back room – claiming them damn girls bought it all ..

What’s not so smart is most of them are selling under the shop account, and was I the Whiting Hackle Company I might want to be bring a couple of those vendors up short, as I have enough troubles keeping the fly tying market in feathers without some sharp SOB hoarding all the good saddles in the back room – claiming them damn girls bought it all ..