The next time someone mentions fly tying you can print the picture at left and insist that rehab is more than you can bear…

The next time someone mentions fly tying you can print the picture at left and insist that rehab is more than you can bear…

I’d said, “jump in with both feet” – and meant it, until the vendor plopped another 300,000 hooks onto eBAY. Now I’m hoping you’ll save me from myself, and scoop them up before I do.

I had mentioned last week about the spectacular ancient Mustad iron being blown out by Har-Lee Rod of New Jersey, and just as I think things are winding down, out comes another load of some incredible old hooks – at prices you’ve never seen – nor will again.

“Both Feet” for us hardcore types was about 50,000 hooks (shown above), most were purchased at $0.99 for 500, about twenty cents per 100 hooks.

A cup of coffee costs more …

Many are kirbed or reversed and digging through all those styles revealed some outstanding gems, most of which have attributes unavailable in the current Japanese iron.

As I watch and bid, I’m surprised at the brainwashing that’s occurred. Traditional fly tying hooks without kirbed point and equipped with the familiar down eye are moving smartly, but most of the other hooks are loved only by the occasional odd duck like myself.

As the fly tying forums have asked the question many dozens of times – and most of the answers are dead wrong, indulge me …

A Kirbed or Reversed hook is merely a method to make the hook gape larger. That’s all.

Offsetting the point to the left (Kirbed) or right (Reversed) makes the distance from shank to point longer than if the point was directly below the hook. Think of a right triangle with a line dropped perpendicular from the shank to where the point should be (in non kirbed hooks), if we draw a horizontal line from that spot to where the Kirbed point is – we’ve formed a right triangle. Everyone knows the hypotenuse of a right triangle is the longest side … therefore the gape is “wider” than a traditional hook.

Outside of forgetting about that offset point and pricking yourself, tying on these “bait” hooks is unchanged.

As quite a few packages are labeled in French, it appears few shoppers are translating the labels. “Hamecons Irlandais” isn’t something exotic, it’s merely French for “Irish Hooks” – and “Hamecons Ronds” translates to “Round Hooks.”

While the obvious fly tying styles are disappearing us continental types are picking up everything ignored or … gasp … foreign, for dirt cheap.

I’ve compiled a list of some of the sweeter flavors available, but as sizes are starting to disappear it’s entirely first come first serve.

Mustad 234B, Hamecons Irlandais 234B

Premiere Qualite = Premier Quality

Noirs a anneau = Black Ring (Japanned finish, Ring eye)

Tige courte = Short Shank (at least 2X short)

Renforces = Reinforced (at least 2X strong)

This is a KIRBED hook

I’ve already burned through a couple of boxes of these gems, tying both Czech nymphs and Shad flies. I’m using the #4’s for a hook that looks like a #6 – hence it’s at least 2X short. I bend down the last quarter of the shank about 10° and it becomes a Czech nymph hook, yet has appropriate extra-strong to go with a fly that is fished amid snags and rocks.

I’ve already burned through a couple of boxes of these gems, tying both Czech nymphs and Shad flies. I’m using the #4’s for a hook that looks like a #6 – hence it’s at least 2X short. I bend down the last quarter of the shank about 10° and it becomes a Czech nymph hook, yet has appropriate extra-strong to go with a fly that is fished amid snags and rocks.

The hook is unforged, so if you don’t like the offset point, bend it back. It’s already twice as strong as the weak Czech wire and you’ll sacrifice nothing in reliability.

Note: It’s only safe to bend an unforged hook, forged wire is much more brittle and is weakened considerably.

The Hamecons Irlandais 267B is the same hook but with normal wire and bronze finish. It is also a Kirbed hook.

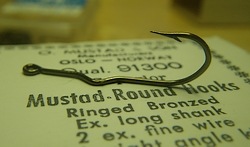

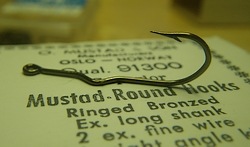

Mustad 91300 – Superb fine wire Bass Popper hook, with no takers due to the zig zag in the shank. The eBAY audience either doesn’t recognize what to do with it, or doesn’t fish Bass – and you get 500 for $0.99.

Mustad 91300 – Superb fine wire Bass Popper hook, with no takers due to the zig zag in the shank. The eBAY audience either doesn’t recognize what to do with it, or doesn’t fish Bass – and you get 500 for $0.99.

Just cut hobby foam into the right shape, slit it down the side, slide it over the shank and throw some rubber cement into the “slice” to hold everything together … add a pinch of saddle hackle and marabou, and you’re done.

Mustad 4450 – A nice Mustad 9671 or Tiemco 3769 substitute. Unforged Model Perfect bend, ring eye, looks like about a 2X long shank (although it doesn’t say as much).

Mustad 4450 – A nice Mustad 9671 or Tiemco 3769 substitute. Unforged Model Perfect bend, ring eye, looks like about a 2X long shank (although it doesn’t say as much).

I am a huge fan of ring eyed nymph hooks and despaired that my vanishing supply was all I was ever to see . Now I’m covered for the next couple of decades, including both even and odd sizes.

No physical reason for “ring-eyed versus down-eyed” – I just like ‘em.

The crowd is wise to the Mustad 9143 Dry Fly hook now – but not before I scored a couple thousand for $0.99 per thousand. Offered in the thousand-pack in size 16, and in boxes for size 18 and 20.

The crowd is wise to the Mustad 9143 Dry Fly hook now – but not before I scored a couple thousand for $0.99 per thousand. Offered in the thousand-pack in size 16, and in boxes for size 18 and 20.

This is a Redditch scale hook and is much smaller than the training-wheels 94840 (Tiemco 100) standard. Recent fly tiers would call the #16 a #18 – so allow for the size difference if you’re used to Tiemco’s or any current dry fly offering.

What the crowd doesn’t know is the Hamecons-Ronds 57552 is even better than the 9143, and available in the odd sizes which will make less of a size difference than a full even number. I stocked up on the #15’s as it is a superb size for my fishing.

What the crowd doesn’t know is the Hamecons-Ronds 57552 is even better than the 9143, and available in the odd sizes which will make less of a size difference than a full even number. I stocked up on the #15’s as it is a superb size for my fishing.

For a great nymph hook, look at the Mustad-Limerick 31250. It’s a 3906B lookalike with a Limerick bend, and most of the small sizes were available.

There’s not too many sizes left of the Mustad 3116A, but there are plenty of size 9 and size 2 left. This was my favorite, 2X strong, down eye, Limerick bend, short shank, equipped with needles for points. Absolutely bestial sharpness. All of my Shad flies are being swapped to this iron immediately. Good strong steelhead and salmon hook, strong enough for big Carp – and was available in all the even and odd sizes until I saw them.

There’s not too many sizes left of the Mustad 3116A, but there are plenty of size 9 and size 2 left. This was my favorite, 2X strong, down eye, Limerick bend, short shank, equipped with needles for points. Absolutely bestial sharpness. All of my Shad flies are being swapped to this iron immediately. Good strong steelhead and salmon hook, strong enough for big Carp – and was available in all the even and odd sizes until I saw them.

For the light wire long shank dry fly, it’s Christmas. There’s a beautiful long shank, fine wire, dry fly hook in the perfect sizes for stonefly dries and big October Caddis. It’s the Mustad 32800, and there’s nothing like it on the current market.

There’s also the occasional 4x Strong or 3X Strong (Mustad 802) hook that have been unavailable for years. Those old codgers in “Rivers of a Lost Coast” have secrets – one of them was to downsize the fly in bright, clear conditions. A 20lb salmon on a contemporary #8 may be ridiculous, but those old hooks with 3X-4X strong attribute were something special.

The rest is up to your avaricious nature. I don’t cover too many subjects a second time, but these are extraordinary prices and will not happen again.

Tags: Mustad hooks, Harlee Rod, long shank, short shank, extra strong, salmon, steelhead, fly tying materials, bulk fly tying hooks, Tiemco, October Caddis, popper hooks, eBAY deals,

If fly tying wasn’t such a mood based hobby your flies would be twice as good. A big order of tiny, upthrust, and gossamer locks the poor tyer into a mayfly mindset and when a big black ant is up next – being a “slab” of protein completely out of place on water, the result is tiny, gossamer, and neat …

If fly tying wasn’t such a mood based hobby your flies would be twice as good. A big order of tiny, upthrust, and gossamer locks the poor tyer into a mayfly mindset and when a big black ant is up next – being a “slab” of protein completely out of place on water, the result is tiny, gossamer, and neat …

The next time someone mentions fly tying you can print the picture at left and insist that rehab is more than you can bear…

The next time someone mentions fly tying you can print the picture at left and insist that rehab is more than you can bear…

Mustad 91300 – Superb fine wire Bass Popper hook, with no takers due to the zig zag in the shank. The eBAY audience either doesn’t recognize what to do with it, or doesn’t fish Bass – and you get 500 for $0.99.

Mustad 91300 – Superb fine wire Bass Popper hook, with no takers due to the zig zag in the shank. The eBAY audience either doesn’t recognize what to do with it, or doesn’t fish Bass – and you get 500 for $0.99.

The crowd is wise to the Mustad 9143 Dry Fly hook now – but not before I scored a couple thousand for $0.99 per thousand. Offered in the thousand-pack in size 16, and in boxes for size 18 and 20.

The crowd is wise to the Mustad 9143 Dry Fly hook now – but not before I scored a couple thousand for $0.99 per thousand. Offered in the thousand-pack in size 16, and in boxes for size 18 and 20.

There’s not too many sizes left of the Mustad 3116A, but there are plenty of size 9 and size 2 left. This was my favorite, 2X strong, down eye, Limerick bend, short shank, equipped with needles for points. Absolutely bestial sharpness. All of my Shad flies are being swapped to this iron immediately. Good strong steelhead and salmon hook, strong enough for big Carp – and was available in all the even and odd sizes until I saw them.

There’s not too many sizes left of the Mustad 3116A, but there are plenty of size 9 and size 2 left. This was my favorite, 2X strong, down eye, Limerick bend, short shank, equipped with needles for points. Absolutely bestial sharpness. All of my Shad flies are being swapped to this iron immediately. Good strong steelhead and salmon hook, strong enough for big Carp – and was available in all the even and odd sizes until I saw them.

The Underwear River Caddis marries the soft hackle and fur collar to traditional shad orange, it’s an homage to classic shad colors with a bit of trout food chaser.

The Underwear River Caddis marries the soft hackle and fur collar to traditional shad orange, it’s an homage to classic shad colors with a bit of trout food chaser. … and for the minnow crowd we assumed a bit of shiny mixed with a lean silhouette would cover all the possible fry that might stumble into a pod of ravenous herring.

… and for the minnow crowd we assumed a bit of shiny mixed with a lean silhouette would cover all the possible fry that might stumble into a pod of ravenous herring.