My theory is fly fishing humor is a victim of the thousand dollar fly rod, as the witty good-natured fellows, the kind welcome in any camp, aren’t drawn to rarified technological marvels, rather they’ve fled the sport to husband cash for mortgages and orthodonture for their offspring.

The below humorist work was submitted by a kindred spirit, who for obvious reasons, insists on remaining anonymous. Aimed at his home waters of Arkansas’s White River, the author has struck a rare chord that resonates for every river anywhere.

Yes. I wish I wrote it.

Kbarton10

Early Sociology of the Region

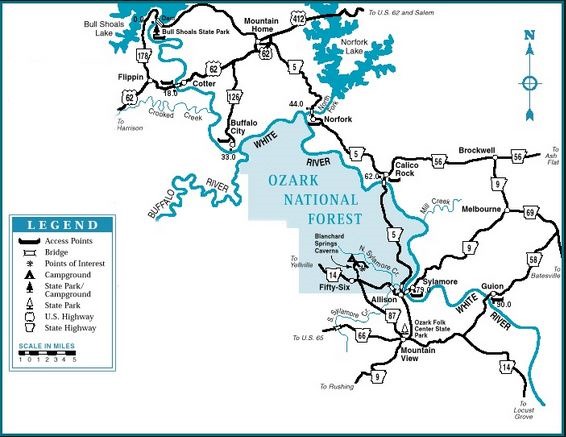

The Upper White River in northern Arkansas is a distinct socio-ecological region that is more than 100 miles from anywhere else, yet equidistant, or nearly so, from most other places. The original non-indigenous Homo spp. fauna consisted mainly of descendants of 19th century settlers derived from a degenerate branch of upland southern Anglo-Saxon stock originating in western North Carolina and Virginia. The intelligent components of this diaspora traveled only so far as West Virginia, where they settled in various coves and “hollers,” and were later known primarily for seeking psychic fulfillment by inhaling gasoline fumes from Mason jars. But that’s another story altogether.

As the early migration continued west through north Arkansas, some of the remaining westward-trekking pioneers, in a profound state of mental and physical fatigue, gave up and said, “Screw it, this is hard, I can’t go any further, I’m stopping here.” In remarkable irony, the worst example of “pioneer spirit” in American history thus settled on the worst farming land east of Death Valley—an area with topsoil so thin “you can read a Bible through it,” as they say.

Given this combination of socio-psychological deficiency and geo-agronomic limitation, it should come as no surprise to even the most careless student of the human condition that the original settlers in the area survived not by farming, but by developing a meager but satisfying lifestyle consisting of the closed-loop, patho-economic activity known as “subsistence-level population self-abuse”—manifest first by selling one another the worst fermented-corn distillate in the southeast and later by selling one another the worst homemade methamphetamine in the United States. (It should be noted, possibly for the safety of visiting flyfishers, that Ozarkian meth “cookers” were not impacted to a significant degree by laws limiting over-the-counter sales of pseudoephedrine-containing cold medicines; local cookers, being what they are, labor on under the impression that all cold medicines are created equal when it comes to meth precursors and have freely substituted other, non-regulated formulations—most commonly Vicks VapoRub, which gives Ozark meth a characteristic mentholated aroma, a physiological non-effect due only to a non-pharmaceutical “contact-high,” as well as the not-so-odd sequala of suppressing coughs associated with the 3-packs-a-day of Marlboro reds consumed by the average Ozarkian meth-chef.)

The unsustainable “perpetual motion” economic model associated with selling mid-altering substances to one another was slowly modified and made thermodynamically plausible first by an influx of retirees from Mississippi seeking asylum from mosquitos and other lowland plagues and, second, by the economic engine colloquially known as “trout fishing.” Trout fishers cut across a wide swath of socio-economic type-species, and may be armed with anything from $900 flyrods to $6.96 K-Mart combo-spincasters, but they have one important characteristic in common: a propensity to spend money as if the Russians were just across the ridge in Harrison.

Salmonid Fisheries of the Region

Species of the family Salmonidae (the trouts, salmon, whitefishes, and relatives) are not native to Arkansas due to lack of suitable thermal refugia after Pleistocene Epoch glaciation. Trout fishing in the White River drainage basin was made possible by construction of a series of dams, starting with Norfolk Dam, on the North Fork of the White River, in 1944. Dam-building was initiated by “New Deal” visionaries to provide gainful employment to Ozarkian society, whose previous experience with applied hydrology consisted of trying to put a cork stopper back in a whiskey jug. The resulting reservoirs, now numbering five, provided year-around cold water that randomly ranges from a trickle to Noahichian flood—in other words, the perfect resource for dangerous southern trout fishing.

The combination of tailwater trout fishing, deceptive remoteness, and the presence of one “wet” county located in the geographic center of a virtual barricade of bible-belt-cum-meth-lab counties attracted fishermen from throughout the midsouth and midwest. There is only one commonality among the millions of potential trout fishers in that extensive circumscribed area: they’ll all be on the river the same day you are, no matter where you fish and no matter what day it is.

The Fishers

Trout fishers are heterogeneous and many classification schemes have been proposed, in both the scientific literature and on the walls of truck-stop restrooms. Here we discuss the most familiar hierarchical grouping, which is based not on supertype-subtype relations for prescribed biological traits, but rather by a simple subtype-subtype grouping that assumes, on the face of it, no hierarchy at all. This classification is based on the type of fishing equipment that is used to capture trout.

A relatively circumscribed subclass uses fly rods, and, with apologies to no one, this subclass will be the main, but not exclusive, focus of this treatise. Nevertheless, and notwithstanding the highly inflated importance that flyfishers often ascribe to themselves, the largest subclass of White River fishers (by total number and average body weight) uses spinning tackle and bait. Fly fishers often identify members of this subclass using the common names “longcods” or “jaggoffs.” Of course, flyfishers, being what they are, mutter these epithets sotto voce, only after the risk of a serious physical beating by three or four drunken baitfishers has drifted a safe distance downstream. The favored baits in the region are artificially formulated plastic-like balls called PowerBait—a generic term, eponymously named after the most popular commercial version of the yellow, greasy material soaked in powerful fish attractants. It is widely rumored, with as yet no scientific evidence, that the Berkeley Company originally formulated PowerBait to mimic both the size and consistency (but not color) of the average bait fisherman’s testicles. This intentional marketing decision was based, it is said, on the theory that copying this anatomical feature would subconsciously induce fishermen to “handle” the bait more often, perhaps leading to greater product usage and higher sales. Also of note, social statisticians have yet to prove, one way or another, whether Ozark guides’ near-universal use of canned corn as chum was the basis for the most popular PowerBait color or whether guides started using corn as chum to mimic yellow-colored PowerBait. This is widely known within the fishing tackle industry as the “Berkeley chicken-or-egg paradox” and serious attempts to discern cause-and-effect have led to madness among at least three doctorate-level sociologists.

Perhaps the defining characteristic of the “spinning and bait fisher” subclass is the fact that these sportspeople will never be seen in their natural setting more than two feet away from an ice chest—universally known in the region, and not without just cause, as a “beer cooler.” The spatial (and special) relationship between human being and beer cooler has been described by some social scientists as the animate-inanimate equivalent of biological symbiosis, although the benefit derived by the beer cooler from association with humans has never adequately been explained, other than the theory that the beer cooler (often a beaten-down version constructed of white styrofoam with a yellow polypropylene rope serving as the “handle”) derives benefit from the relationship by being able to “see the world” while attached to a spin fisherman. This superb example of attaching an anthropomorphic reward system to an inanimate object was recently discredited when it was discovered that Yeti-brand coolers provided greater benefits to the human than that derived by the cooler from the human.

Another, smaller, fisher subclass frequently seen on White River trout fisheries uses spinning tackle and large artificial lures. The most popular lure used by Ozarkian trout fishers is the “Countdown Rapala,” a lure that looks like a gang of boat anchors attached to a small, colorful baseball bat. Anglers in this subclass typically stand, rather than sit, in boats while drifting downstream, casting great distances in hopes of either snagging the waders of flyfishers or, possibly, catching spawning brown trout. Either outcome is considered equally rewarding. Rapala fishermen are an important ecological “forcing factor” shaping fish community structure. Brown trout comprise a naturally self-sustaining fishery in these rivers and if adult brown trout were unharvested, these food-rich rivers would sustain perhaps the greatest population of brown trout in the world. This notoriety would, of course, attract untold numbers of fishers to the area, which would seriously disrupt the local social structure and service-based economy by inducing development of an increased number of liquor stores, as well as attracting additional females and males engaged in prostitution. Rapala fishermen thus serve as a significant influence on stream ecology (and, by extension, local socio-economics) by removing spawning adult brown trout (when spawning, brown trout are easier to catch than the flu in an elementary school restroom). Continuous and persistent removal of spawning fish assures that the ecosystem will be populated with many very small fish—primarily recently-stocked, hatchery-grown rainbow trout—that are considered “best eating” by longcods and related fisher-types, and also assures that the fishery will not attract undesirables interested in a truly quality fishing experience, as well as other associated diversions.

It is perhaps worth noting, or maybe not, that no study has yet been conducted to determine the genetic relationship between White River longcods and tournament bass fishermen, despite the appeal of connecting what appears to be two divergent lineages with a probable common ancestor. The near-sexual affection shown by both subclasses for large, overpowered watercraft is possible evidence of this genetic linkage. Additional similarities include failed attempts to hide obesity-related double chins under goatees and lack of social remorse when wearing vented shirts to their mother’s funeral. The lone behavioral disconnection is the apparent requirement for glittery watercraft by bassfishers and the non-requirement of highly ornate watercraft by longcods. This disconnection hints at either a lack of genetic similarity or, more likely, genetic divergence from a common ancestor. One theory posits that both subclasses derive from sexual liaisons between humanoid New-World mammals and Spanish Conquistadores, who, it has recently been discovered, came to the New World in search of gold, not for personal enrichment, but rather to be ground into a fine powder and sprinkled liberally over their lateen-rigged caravels in an attempt to impress Cadiz prostitutes when returning from long voyages. This is thought to be the first example of what eventually evolved into the bass fishing “glitterboat.” Careful examination of a recently discovered oil painting of Christopher Columbus lends credence to the theory of an Italian/Spanish ancestry for bass fishermen (if not longcods), as it was revealed that the shirtwaist worn by Columbus while sailing across the Atlantic was adorned with many cloth “badges” and “patches” with embroidered writings such as “I Heart Isabella” and “Dee Colombo Cheese Shop” (the latter an open admission that his voyage was partially subsidized by proceeds from the cheese shop owned by his father, Dominico, in Savona). Modern-day bass fishermen have retained this mode of dress, and fishing jerseys are now adorned, much in the manner of Columbus, with logos for various tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, and internet porn sites, as well as sporting clever phrases such as “Bass Fishing—Size Does Matter.” Another common badge worn by bass fishers—with no sense of cynicism, hypocrisy, or irony—reads “Take a Child Fishing.”

Arkansas Fly Shop Personnel

The propensity of flyfishers to spend vast, obscene sums of money on arcane and relatively useless paraphernalia provided economic-development opportunities based on the capitalist conditional model of “never let a dollar be left unspent” and, as such, fly shops have exploded in number in the Mountain Home metroplex, much like mushroom rings around manure piles in poor pasture soils after a rain. Fly shops are, of course, small specialty stores that sell cheap fingernail clippers (re-labeled “line nippers”) for $8.50, little round pieces of styrofoam (re-labeled as “strike indicators”) for $5, and plastic fishing rods that cost several times more than your first car. Despite an attractive business plan based on retail markups of several thousand percent on all items (a practice specifically banned in the Old Testament book of Leviticus), the half-life of the average north Arkansas fly shop is something less than 11 months. The short half-life is not, however, due to the lack of wallets attached to flyfishermen or the willingness of those wallets to regurgitate for overpriced merchandise. Rather, the continuous wax and wane of shops is due to the retail dilution effect caused by the region having more flyshops per capita than anywhere east of West Yellowstone, Montana. The other factor influencing flyshop profits and the high turnover rate is persistent customer dissatisfaction with the way they are “serviced” at each new shop. Here we use the word “service” in much the same way that ranchers use the word when they take a bull to another ranch to “service” a heifer. So, in this section, we will discuss the providers of fly shop service; that is, the typical fly shop worker. This subclass of troutfishing fauna is so unique that it deserves further discussion before proceeding with a more complete description of faunal subclasses not formally engaged in the “service” sector of flyfishing commerce (that is, those being “serviced”). In particular, we will show that fly shop workers in Arkansas form a distinct group that science has recently proven to be psychologically, and perhaps genetically, distinct from fly shop owners in other regions. Of interest is the effect, or non-effect, of customer place-of-origin on fly shop worker behavior.

(Note that “customers” are never known by that name in the flyfishing retail business, but rather they are universally referred to as “sh*t-heels” among fly shop workers whenever they discuss business among themselves. Here, however, we will use the less profane epithet “customer” to describe people who wander, intentionally or accidentally, into fly shops. Further note that purchasing flyfishing equipment is one of only two retail transactions known to man where the items purchased weigh less than the paper money used to make the purchase. The other retail transaction where this occurs is when you buy helium balloons for your kid’s birthday party)

To the uninitiated, fly shop workers in Arkansas appear to be cut from the same cloth as fly shop workers everywhere, as if all are trained in one central location, perhaps in France. That is, they possess a rudeness that seems borne of clinical-grade constipation, and a small smile breaks free only when the customer exceeds some pre-defined spending limit—which ranges from $250 to more than $1,000 at the more upscale shops (easily identified by the ‘Sage’ and ‘Simms’ signs lining the storefront). These are, by the way, the same people who will let you ride in their boat for $500 a day while they smoke the vilest cigar south of Cleveland, Ohio, and piss on your boot when you do not tip an extra 25% for the ham sandwich and warm Yoo-Hoo provided at lunch. (With respect to flyfishing guides’ seemingly universal and insatiable appetite for oversized, foul-smelling cigars, remember what Sigmund Freud’s secretary—Krystal Friedrickson—often said when returning gingerly from her boss’s office: “Sometimes a cigar is NOT just a cigar.”)

For many years, it was believed that fly shop worker behavior was due to loss of eyesight and/or loss of hearing, perhaps related to constant exposure to solvents in fly-tying head cement or, possibly, silicone in fly floatants. Blindness, either partial or complete, coupled with partial hearing loss would, in fact, account for at least one aspect of the behavior of fly shop workers, wherein the customer is completely ignored until repeated verbal requests for help are finally acknowledged with phases such as “Huh?” or “ Whaddya want?” Blindness alone would not, however, account for one odd aspect of typical behavior, wherein the customer’s request for information on “What fly are they hitting?” is always—always—answered by “Olive Wooly Buggers,” spoken in the same curt, dismissive tone of voice normally used to answer a leper’s request for directions to the nearest water fountain. Often, the fly shop worker’s reply is accompanied by a particular facial expression that is, in fact, described as part of the “Universality Hypothesis” first proposed by Charles Darwin in his work “The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals.” This facial expression was added to so-called “universal” expressions of happiness, anger, fear, and sadness, and was given the now-accepted descriptor, “I smell dogsh*t.” Further, the quality of information on effective fly patterns changes dramatically when the same question is asked while the customer is placing a large amount of merchandise on the check-out counter. Suddenly, and especially as the ongoing purchase exceeds several Franklins, exquisite details begin to flow from the previously mute salesperson: “Go two hundred and twenty yards below the new Cotter Bridge; fish are crazy for a size 18 Ruby Midge fished 27 inches below a pink strike indicator between 3:30 and 5:00 on days containing the letter ‘u’.” If the purchase exceeds $1,000, behavior becomes even more radical—rapidly changing from forthcoming to positively syruppy: “I’ll even take you there if you want, and carry your rods. Do you need any drugs? Women?” Such anomalies in response-quality rule out blindness or hearing loss as a basis for boorish behavior.

Two recent studies of cognitive behavior therapy sought to understand the neuro-biological basis for the acute interpersonal-relationship dysfunction almost universally seen in fly shop personnel. To elaborate a point, the behavior was described above as “rude” but it goes far past that simple classification. In the at-large population, some manifestations of rudeness are inadvertently, and sadly, borne of lack of cultural interaction, lack of education, or surgical removal of certain brain parts. However, the rudeness we speak of here is plainly a matter of intentional churlishness or insolence, almost as if social-class dysfunction were at the base of the behavior. The first indication that social-class status was not, however, involved in fly shop rudeness was the study of Dr. Simon Crabbwalk, retired professor of post-modern paleoanthology at the University of California, Coalinga, who showed that the mean income level for parents of fly shop workers was within one standard deviation of average for the population at large, although average educational achievement did fall slightly below one standard deviation of average for the at-large population. The conclusion of this study is straightforward: it is doubtful if real or perceived social or educational superiority is the basis for antisocial behavior among fly shop workers.

Further research by Professor E. Tathawhy at the University of East Texas at Amarillo traced employment outcomes of a large set of individuals with common upbringing. His work showed that people with certain traits naturally and systematically gravitate towards specific employments opportunities. Oddly, fly shop workers formed perhaps one of the tightest clusters of personality trait-types in the study. In his webinar presentation at the 3rd Annual Virtual Meeting of the National Associations of Rational Emotive Therapists and Professional Fly Casting Instructors, Dr. Tathawhy summarized his findings thusly:

“Fly shop workers do not, in fact, come from a random population, but rather from a well-defined subclass of people who, from childhood, can be scientifically classified as “assholes.” Further, they do not randomly move into certain employment opportunities, but rather, they actively seek employment in settings that allow their behavior to be fully expressed. In other words, fly shop workers are “born into it” based on a genetic predisposition for assholedness. In fact, my work showed that given lack of opportunity for employment in fly shops, this population subclass would be compelled to find employment in other sectors that tolerated, and even rewarded, their behavior, such as working for TSA at major airport hubs or for the DMV at driver’s license-renewal stations”

Two years later, an undergraduate student—Felix Hundschiessen-Jones—at the University of Arkansas satellite campus at Mountain Home, noted that Dr. Tathawhy’s work involved samples only from the western United States (primarily northern California and the circum-Yellowstone area of Montana, Idaho, and Montana). Mr. Hundschiessen-Jones’ senior-class thesis therefore focused on fly shop workers in the north Arkansas area and his conclusions are diametrically opposed to those of Professor Tathawhy. North Arkansas fly shop owners do, in fact, come from a random population with respect to parental income, educational achievement, and even the so-called AQR (Asshole Quotient Rating) developed by Dr. Tathawhy. The startling conclusion of the work by Mr. Hundschiessen-Jones was that the rude, boorish, and discourteous behavior seen in Arkansas fly shop workers is developed over time—a sort of on-the-job-training in insolence. Several retired fly shop workers in the Cotter area who were interviewed for the study indicated that the slow downward spiral from normalcy to churlishness could be blamed on anglers from Mississippi, who shop for long periods, fondling $1500 bamboo fly rods and $500 Ross fly reels that they clearly could not afford, and then ask to use the store’s restroom, an activity followed by outbursts of “bathroom sounds” clearly related to a recent meal containing either refried beans from Letties in Gassville or crab rangoon from the all-you-can-eat Chinese restaurant in Mountain Home. After non-productive browsing and productive physical relief, the angler, often wearing waders and wet, muddy boots, would approach the checkout counter with two, size-16 Chuck’s Emergers in a plastic semen-sample cup and ask if he can pay for the two flies with an out-of-town check. “How,” one former fly shop worker asked, “can sanity be maintained when the customer base consists of so many Mississippi ‘flyfishermen’?” This question has, of course, no answer based on rational thought, but the point was this: Rather than engaging Mississippi flyfishermen in unproductive and inane discourse, it is best to pretend they do not exist at all, except as part of a bad dream that would hopefully all go away when morning comes. But it never does.

The “Generation Schedule”

When people from outside the region fish in the White River area, they naturally expect the nose-in-the-air, neo-bourgeois attitude that has come to define trout flyfishers throughout the United States. This behavior originated in males who were constantly bullied in high school and then discovered one thing they could do better than actual athletes—wave a long, thin piece of plastic back and forth and catch an animal with a brain no bigger than a black-eyed pea. Good examples of this sort of psycho-sexual rod-length overcompensation are, in fact, easy to find on the White River system. And the behavior seems universally manifest in travelers from Dallas, Memphis, and Kansas City. In an odd coincidence that has not gone unnoticed by social statisticians, these cities are also home to large concentrations of people who make delusionary claims that their city has “the best barbeque in the country.” Only one parsimonious theory has been offered for this correlation: being a snob is not confined to either fishing or food. By the way, the terms “good barbeque” and “Dallas” seldom appear in the same sentence, for the same reason that the terms “Nobel Laureate” and “Arkansas” are usually separated by at least several book covers.

But, all that is one thing. The behavior we speak of here is something quite different: an edgy, nervous demeanor that seems unique to White River flyfishers. The behavior is manifest only when Ozark flyfishers are on the river, especially when alone, and is superimposed on the snot-nosed attitude common to all flyfishers when they are in the company of other human beings, or dogs. Clinical signs are obvious, distinctive, and nearly universal: semi-continuous to continuous head and eye movement looking upstream, downstream, and across stream, accompanied with sudden darts towards the bank when changes in wind direction cause river sounds to wax and wane. Psychologists have compared this erratic behavior to that seen in men who expect the husband of the woman they’re screwing to pull up in the driveway at any moment.

The basis for this human behavior is the random and spectacular change in water flow experienced on these tailwater rivers as either more, or less, or even much more, water is released from the damsite through turbines used for generation of electricity, or something. Hydrographs of the Bull Shoal and Norfolk tailwaters resemble an EKG recording of someone in the midst of acute ventricular fibrillation—spikes of wild magnitude with irregular flatline periods that, for hydrographs, correspond to periods of safe, wadeable water followed at random intervals by sudden releases of torrents that raise the river levels by several feet in a matter of minutes.

When north Arkansas flyfishers meet in morning, no one says “Hello” or “Good morning” but rather the common greeting is some version of “What’s the generation schedule?” The deeper, unspoken question is “Will I drown today?” The only truthful answer to either question is a reciprocal, rhetorical question: “Who in hell knows?” And perhaps someone in hell does know, because no one else does.

Attempts to interpret the scientific basis for the seemingly random rise and fall of the river usually take into account sound scientific factors such as the regional need for electricity generation, reservoir water levels, downstream flood control, astrological signs, bird migration behavior, and nut storage by squirrels. The best current theory is that the generation schedule is set by a Corps of Engineers technician who caught his wife red-handed (or perhaps some other body part) during a physical liaison with a flyfisherman. Instead of blaming his wife for bad taste in men, he took his revenge by managing water flows in these streams to minimize flyfishing opportunities while maximizing the probability of drowning as many flyfishers as possible.

In an attempt to avoid litigation, while simultaneously engaging in relatively intense schaden freude, the agency charged with managing water flows has established websites and telephone “hotlines” that offer, on the face of it, hydropower generation schedules for the tailwaters. These information portals also have links to Las Vegas “tout” services for betting on NFL football games as well as advice on paramutual wagering for horse racing and cock fighting. Many people, especially newcomers to the area, actually rely on hydropower generation predictions to determine where and when they can safely fish, despite the fact that recent statistical studies have shown that predictions against the point spread for NFL football are 2.7 times more accurate than agency estimations of hydropower activity. The agency has, so far, avoided criminal and civil litigation by prefacing their voice-activated telephone reports with the message, “Estimated generation schedules should NOT be relied upon to predict safe water levels” spoken in a computer-generated voice, complete with laughing sounds in the background. Most experienced flyfishers now use more accurate methods of determining safe wading conditions, the most common and reliable being Tarot cards or coin flips.

So, over time—and despite denial by Baptist ministers—evolution based on a sort of brutal Darwinism caused all north-Arkansas flyfishers who are currently alive to develop erratic, nervous behavior patterns. Despite previous studies of flyfisher neurophysiology indicating that this behavior was physiologically related to functioning of the well-known hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the resulting “fight-or-flight” response, recent studies using advanced brain-imaging techniques have shown conclusively that there is no “fight-or-flight” response in most flyfishers but rather, simply “or-flight.” That is to say, and in layman terms, the basis for the widespread development of this set of traits is not behavioral modification over time, wherein repeated exposures to stressful stimuli (unexpected, rapidly rising water levels leading to repeated near-death experiences as waders fill with water) cause ever-increasing cortisol or blood glucose production, but rather it is based upon the simple genetics of “individual selection”—a breeding program often used to produce commercially useful changes in cattle or swine. Fundamentally, if you are not watchful, you die. And if you die, you cannot procreate. This straightforward example of “non-survival of the non-fittest” typically ends when a redneck teenager finishing his fifteenth Keystone Light finds your body hanging from the low-water dam 50 miles downstream in Batesville.

Human “Trout-Fishing” Fauna of the Region

Notwithstanding initial impressions of the indigenous human population, which usually makes newcomers feel that they have somehow accidentally wandered into the middle of a casting call for extras in “Deliverance II,” the human trout fishing fauna of the upper White River ecological area is, in fact, as varied as it is abundant. Although it appears, and it may be true, that there is a seemingly endless mass of humanity stretching from Red’s Landing to Red Bud on any given day, nearly 93% of the fauna fall into one of five general taxa. Presented below, for the naturalist specializing in such things, is a dichotomous key to the major faunal groups seen on the White River below Bull Shoals, and to include the North Fork of the White River below Norfolk dam.

The Key

Users of this key should be aware of the substitutability of the specific epithets; for example, “Oklahoma City Family Man” is simply one of a group of similar taxa that may include, to name a few, “Tulsa man,” Muskogee Man,” and even “Enid Man.” As such, “Oklahoma City Family Man” can be considered the type species of a species-group of related taxa. The same may be said of the type species “Fort Smith Chapter of UA Alumni Association,” which is nearly indistinguishable from many other University of Arkansas alumni groups, most of which consist predominantly of clinically obese males who have never set foot in Fayetteville except on autumn Saturday afternoons. In fact, individuals with the most pronounced features of the species in general are almost always false-species—a sociological analog of the ecological principle of mimicry, or mimetism. In ecology, mimicry describes a situation where an organism evolves over many generations to share common physical characteristics of another group. Sociological mimicry—most strongly developed in so-called University of Arkansas or University of Alabama alumni—consists not of genetic changes leading towards some common set of physical attributes, but rather a sort of false belief, or delusion, that the person actually attended the school in question. In extreme cases, the mimic may, in fact, be unaware of the false nature of the belief, even to the point of maintaining that he “lost his diploma in the flood of 1974,” despite being only 8 years old at that time.

The one exception to this so-called “cross-characterization by specific example” that is used in this key will be “Rhodes College Reunion,” which has been found to be monotypic. As such, the “type species” for this faunal grouping is also the only species yet described. Other small liberal arts colleges in the midsouth have not yet developed distinctive markings and “tells” that allow accurate, consistent diagnostic identification. As such, and perhaps luckily, this remains the only such grouping in this category.

The Key to Fishers of the White River

Instructions: Use as you would any dichotomous taxonomic key. Observe the specimen in question closely, then start at numeral one and choose the most appropriate description from among the two choices. Then go to the number indicated for that choice and repeat the process. A complete description of the particular specimen in question is then appended below the key.

1. Angler’s vehicle has copy of “Home Waters” on dashboard = go to 2

1. Angler’s vehicle without copy of “Home Waters” on dashboard = go to 3

2. Angler with goatee, gold necklace bling with “vasectomy” medallion, and speedo pantylines showing through tailored Simms neoprene waders = Memphis Slicker

2. Anglers in groups of six or more, wearing black rubber “work-boot” waders, using old Fenwick fiberglass rods = Rhodes College Reunion

3. Angler using spinning tackle, clear “fly-and-spin bobbers,” and size 8 McGinty fly patterns at old boat launch area of Rim Shoals = Oklahoma City Family Man

3. Angler not as above = go to 4

4. Anglers fishing from boat, with “hog-hats,” 96-quart cooler of Bud Light, two cans of Sam’s Club creamed corn, and ultralight spinning rods armed with size 6 Slater’s chartreuse crappie jigs = Fort Smith Chapter of UA Alumni Association

4. Angler fishing from boat with Zebco closed-face spincasting reel and nine-inch Countdown Rapala in yellow perch coloration, with female companion wearing “I F*** on the First Date” halter top = Little Rock Air Base Weekender

Annotations: Expanded Descriptions of Fauna

Memphis Slicker

Little known fact: there are more flyfishermen in Memphis than in the state of Montana. Well-known fact: there are more assholes in Memphis than in most cities twice as large. These two facts, standing alone, pose no problem to American civilization. A problem derives, however, from the following logico-algebraic phenomenon: the Venn diagrams for these populations dangerously overlap, and the blue and yellow circles representing the two populations carve out a massive green, lens-shaped area that describes a sub-population of asshole-flyfishing hybrids that seems drawn to the circum-Cotter area like a Collierville wedding ring to a magnet. The slicker is simply one representative incarnation of the overlapping Memphis populations and the following describes only the type-species for this relatively heterogeneous sub-population.

Before each fishing trip, this guy starts a week-long regimen of stomach crunches to prepare for the evening hatch of babes at either the Brass Lure in Cotter or the Elbow Room in Mountain Home. Over time, this regimen of physical training has made less and less impact on his burgeoning waistline. But he knows he looks fine and remains confident that the local “hickettes” will fall down with their legs in the air when anyone from “The City” walks in looking that good. It’ll be all catch-and-release, however, and he’ll make good use of his “latex caddis” lubricated with Gerhke’s Gink because he already has two ex-wives in Germantown and his “equipment” (which he calls his “size 8 emerger”) has a characteristic lesion that will make it a lead-pipe cinch that even a 14-year-old chick from Yellville would be able to pick him out in a Mountain Home “short-arm line-up.”

On the stream, this guy’s got it going in every way possible: eight-foot, four-weight Orvis Helios; Sage large-arbor reel with 400 yards of spun-gel backing, Scientific Anglers Sharkskin “High-Earth Orbit” fly line, twenty gross of the best, individually autographed House of Harrop flies arranged alphabetically in CF flyboxes. His waders are from the new Simms “Millionaire Line” of high-end fishing accessories. The waders were re-cut and custom tailored by “Bruce” back in Bartlett to show off his “glutes” while double-hauling his line half-way from White Hole to White Station. Yet oddly, the slicker never does better than a few stocker 9-inch rainbows per day, probably due to his habit of constantly looking into the edges of his polarized sunglasses to see if he can catch a glimpse of himself rather than paying attention to his bobicator-and-scud setup.

Rhodes College Reunion

These are the same guys who knew a cummerbun from a come-hither when they were 3 months old, yet they show up on the river looking like a road crew out of Varner. But this is not the usual bunch of unwashed covites typically seen up and down the river: There are more unfinished novels among this group than on a mile-long stretch of sand at Orange Beach in July, more degrees per capita than a box of rectal thermometers from Big Lots, and more lawyers than a Vioxx convention. Why then, do these guys “hick-down” so much when the reach the riffles? They don’t trout fish, that’s why.

One guy saw the movie “A River Runs Through It” from atop a Georgia Tech coed when he accidentally left the TV on in his “Motel 6” room after closing down the John Deere hospitality suite at an industrial development conference in Atlanta. A week later, while relating the five-minute affair to his buddies, he flashed back on bits and pieces of the movie and asked where the nearest trout stream was. One of the pals remembered a copy of “Home Waters” left by his father in the back seat of the hand-me-down Mercedes S-350 sedan he’d been driving since his birthday last March. Captured by the phrase “The holiest of waters . . . .”, a quick trip was arranged with reservations for ten in the “big room” at the Y Cabins in Salesville. A rich farmers’s son from north Mississippi “borrowed” eight pairs of black rubber work waders from his Daddy’s catfish farm crew. And the lawyer from Tupelo found a cache of old Fenwick fiberglass rods at an estate sale in Jumpertown while trolling for Baycol clients. The group then cobbled together enough Pflueger reels and level 8-weight K-Mart floaters to make a go of it. A quick mid-route stop at the Heber Springs Orvis Shop provided three spools of 4x tippet, a dozen size 6 Olive Wooly Buggers, one Orvis cap, and a half-dozen Orvis-logo wine-glass snuggies. They made room for the tippet spools in one of the SUVs by consolidating some of the half-empty booze bottles and the crew was then ready to hit the road for a pre-fishing night of collegiality at the “Y”.

The next morning, despite nursing hangovers and the horrible combination of a plugged-up toilet and at least one clinical-level case of the “Y-Grocery microwave burrito two-step,” these guys hit the water like D-day—all sound and fury. But they always stop short and fish over the yellow gravel in foot-deep water. Structure? That’s plot analysis in Lit 401, right? They like Rim Shoals because there’s something vaguely homoerotic in the name. They drink Milwaukee’s Best during the day because of a need to feel “connected” with the “common man.” But there’s always a few bottles of good chardonnay or fume blanc in the fridge back at the Y. This is a good group to hook up with late in the day. They quit early to begin marinating the pork loin and they always drink good scotch.

Oklahoma City Family Man

Fed up with the demands and formalized social structure of the tenth grade, this young man pursued the American Dream at the Muffler Man shop off of Central Avenue, in El Reno. The shop had the privileged location next to the only Taco Bell between Oklahoma City and Amarillo, and, as such, the future seemed as boundless as the Oklahoma plains. Despite being underage, or perhaps because of it, he met his future wife in Bobbie’s Country Kicking Bar and Bait Shop on Route 281 in the northern suburbs of Binger OK, on the banks of the Canadian River. Although he was curious about the close resemblance between this young lady and an aunt on his father’s side, he was thoroughly smitten—in part because her mullet was so much prettier than his. Courting slowly, the first son was born nine months later, coinciding as it did with the four month anniversary of the wedding and reception at the Calumet Civic Center. The next child was delivered eleven months later, after a session of genetic counseling at “Mother Maxine’s Palm Reading and Family Life Center.”

Suddenly faced with a wife and two kids, life had closed in rapidly and his dreams of moving from manifold work to tailpipes seemed trashed at a tender age. Desperate for a break in the cutthroat world of muffler repair, he moved the family east on I-40 to Del City—the economic hub of the Oklahoma City megalopolis—and took a career-starter job with Midas. Nevertheless, he could not shake the ennui of the plains. Boredom, and frustration from not being able to grow a moustache at the age of 19, smoldered deep in his soul, until the only way out seemed to be to get away from the hurry-up world of Del City and take a weekend family vacation.

Fighting the Okie’s genetic hatred of the Razorback Nation, he felt drawn to the cool woods and clear water of northwestern Arkansas after Bill “Eight Fingers” Whiteagle—the shop’s half-Cherokee welder—described a halcyonic weekend involving a home-made porn DVD starring himself and a Waffle House waitress filmed at the Mountain Home Holiday Inn. Although our young man had never fished before, the vague recollection of meeting his wife in a bait shop planted the seed of a notion to go trout fishing. The long weekend over Memorial Day was set as breakout time and, late on Friday afternoon, with greasy soot still under his fingernails from last minute work under a 1983 Cadillac Seville, the family of four (total age = 37 years, which, in a coincident worthy of Guinness, matched the family total for number of toes as well as teeth) boarded the pit bull with the Roto-Rooter guy in the trailer next door and laid skid marks in back of the Z-71. A brief stop at the Piggly Wiggly near the front gate of Tinker Air Force Base afforded time to pick up the vacation essentials: four cartons of Kools, a 48-can suitcase of Bud Light, three packs of disposable diapers, and a case of Hormel canned chili (half of which was “mild,” without beans, for the babies).

Coming up short, still eight miles from Mountain Home, the family stopped in mid-highway and stared at the leaping rainbow trout painted on the blue-background of the Cotter water tower—a vision never seen on the plains. Blaring horns forced a quick turn towards downtown. Although initially struck dumb by the vision of a skyborn leaping trout, he was also fascinated by the name “Cotter”—a word that was reminiscent of some eroticism he has heard in the past, possibly from his wife’s gynecologist at the El Reno drive-in family clinic. Or maybe it was just a remembrance of something to do with the guy in “Urban Cowboy”—his favorite movie from the classic era of Hollywood. The boat dock at Cotter Springs was full of young teenagers swimming in the spring hole, and he was embarrassed about being the same age as the kids, but toting around two kids and a wife, who suddenly looked like a girl from Binger, which in fact she was. Moving on, a short ride down the road delivered him to Rim Shoals, and then back up the road when he was told this was “fly-only” water. After asking around town what “fly-only” meant, he was directed to the Gassville Grocery where the check-out line provided a couple of “spin-and-fly” bubbles, a six-pack of size 8 McGinty’s, and a copy of the National Enquirer for his wife. The McGinty’s looked just like the hornets swarming around the port-a-potty at Rim, so he knew they would be just his ticket to a “limit,” not knowing at the time that Rim Shoals is the center of the Arkansas catch-and-release universe. Some social scientists interpret his choice of fly pattern as evidence that the drive to “match-the-hatch” is an instinctive, rather than learned, behavior.

Among the human fauna inhabiting the White River ecological area, the family man is easily recognized from his habit of constantly trying to maintain a deniable distance between himself and his family, just in case a local halter top walks down the boat ramp. After all, he is only 19—the peak of his sexual prowess, as science has proven. However, the babies and wife always try to follow, so the family man covers a lot of water while fishing. The day always ends as frustrating as it begins: teenagers are having boy-and-girl fun just upstream and here he is, sunburned and hung over, taking grief from his wife who insists on standing on his “casting side” while bitching about going back to the motel. One nice thing: all the used diapers scattered along the bank—well screw ‘em. That’s why they run water from the dam every night—to flush all the accumulated debris from a day of fishing down to Baton Rouge. This is the fondest memory our family man takes home, and why he comes back every year—each morning on the White River starts anew, with a stream bank washed free of family obligations.

Fort Smith University of Arkansas Alumni Association

This six-pack of 18 ACT scores and general business BA’s makes the trip to the White at least once a year—in the fall when the hogs plays Mississippi State in football (“A lock! Who cares?”). Armed with their best crappie rigs, they surreptitiously follow the guides down river every morning and attempt to discover “secret holes” that they are convinced are known only by the local teenagers hired as guides by the resort that begs for a class-action lawsuit for the motto, “It costs no more to go first class.” These guides represent the best example of north Arkansas’ economic-recovery plan, which consists of wholesale transfer of money from the pockets of out-of-state fishermen into the Cotter-Mountain Home twin cities enterprise zone. White River guides have, in fact, been a model for research by Dr. George Butsavitch, emeritus professor of economics at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, who team-teaches “Factors Associated with Social Upward Mobility of Ozarkian Lower Classes”— a crip course taught during summer semester to basketball recruits trying to qualify academically. Typically, Ozark guides defy existing models of professional development and upward mobility by jumping straight from a destiny of keeping flies off a bar stool in Gassville to the open-ended existence of sitting in the back of a boat sipping a Mountain Dew and earning $75 per hour by now and again yelling “cast over yonder by the corn.” Notwithstanding initial impressions when first meeting an Ozarkian guide, visiting flyfishers should perhaps be aware, or perhaps not, that the requirements for becoming a guide on the White River system are, in fact, quite demanding: 1) ownership, or at least possession of, a johnboat whose leaks do not pose an immediate threat of sinking; 2) ownership, or at least possession of, a deafeningly loud and oversized outboard motor; 3) a 24-pack of shear pins; 4) a pint of white paint and a small brush for painting “Red’s Expert Flyfishing Guide Service” on the boat’s side (nearly all Ozark guides are nicknamed Red, for various reasons, and all guides consider themselves “expert”); 5) ownership of a can opener for accessing cans of chumming corn; and 6) the ability to pronounce “Wooly Bugger” correctly (much like pulling the string on a baby’s doll and having it say “Mama,” all Ozarkian flyfishing guides—as also described above for flyshop personnel—respond “Olive Wooly Bugger” when their string is pulled by asking “What are they hitting?”—so they may as well be able to pronounce the fly’s name).

However, and resuming our descriptive narrative, even when our alumni group makes their best effort to emulate resort guides’ tried and true methods of “packing and chumming,” it does not produce the desired result of three limits per day per person—a common feat among the better White River guides who buy metric tons of “chum-grade” corn “short” on the Chicago mercantile. In fact, so much canned corn has been purchased by White River guides that airplane compasses are now equipped with a computer program to compensate for the magnetic deviation produced by tons of empty steel corn cans buried in the Baxter County landfill, which is now considered to be the most iron-rich mineral deposit south of the Mesabi Range in Minnesota. Also interesting, at least to students of aquatic ecology, thousands of acres of bankside “johnson grass” seen along the lower White River during low-water years are now known to consist of immature corn plants derived from kernels tossed into the river by guides a hundred miles upstream. Research by Arkansas Tech scientists has shown that most of the corn kernels shoveled into the river by White River guides would eventually be consumed by trout or other fish, and not reach the lower stretches of the river, if it were not for the widespread practice of “packing.” The technique of packing was initially discovered by one of the original Gaston’s guides—Billy “Five Limits” Bohannon—who found that corn chumming alone did not guarantee the 100 fish-per-day-per-boat that Gaston’s clients expected from top-rung guides. Packing consists not of what you may expect, but rather a guide tossing a half pound of Jolly Green into a hole upstream of some sort of structure and then idling his boat slowly downstream to pack the trout against the barrier before yelling, “Cast quick, dammit.” Not only does this practice concentrate fish into a shockingly small area, making the fishing experience akin to angling in the Atlanta Aquarium, but it also seems that prop turbulence induced by the guide’s 100-hp Merc disturbs great quantities of benthic corn, initiating the downstream niblet drift and subsequent bankside growth of enough volunteer corn to feed a small African country.

The Alumni Association’s failure to emulate the fishing success of young White River guides probably results from the fact that, even after five years of annual pilgrimages, they haven’t learned that guides use “whole-kernel” corn, and that the creamed corn they use has only three recognizable pieces of corn per can and that chartreuse crappie jigs only loosely “match the hatch” of the dull yellow, yogurt-like substance they toss out over the river. Floating dangerously low at four clinically obese alumni per boat, the guys often resort to chumming with bits of the pimento cheese sandwiches packed by their wives; the thought being that chartreuse jigs sweetened with fluorescent yellow Power Bait look more like grated cheddar cheese than creamed corn. The last half of the day is spent in a Bud-fueled stupor, drifting aimlessly downstream with empty Power Bait jars floating in bilge water taken over the low freeboard, along with puke, re-fermenting beer, and empty Ding-Dong packages. However, it’s all in good fun. Until, that is, the boombox batteries begin to give out and “Freebird” slowly grinds to a stop. The boys know, deep inside, that human beings have been known to live for weeks without eating, days without water, and even minutes with oxygen. But all those human limitations pale when compared to life without Skynard.

Little Rock Air Base Weekender

Among all the dudes, mullets, covites, and ‘necks that inhabit the White River biome, this is the easiest species to identify. Crew-cut with a distinct but almost unnoticeable rat-tail, aviator shades, cheesy half-assed moustache, pressed Levi’s, and a black “wife-beater” undershirt emblazoned with the “North Little Rock Harley Shop” logo. What else could it be but Airman, Second Class, from LRAFB? The classy chick with the “Yield” sign” tattoo on the inside of her left thigh and the tattoo of Woody the Woodpecker pushing a lawn mower on the inside of her right thigh is not an Air Force wife, but rather the top half of a barstool from “Beaver Liquors and Lounge” in Beebe. He met her last Tuesday on “Ladies Night,” woke up with her on Wednesday in the Gilhharja Motel on Highway 67 in Jacksonville, and instead of buying her breakfast, promised a trip to Mountain Home. This is not a fishing trip, by the way, except in the loosest meaning of the word.