That last comment was innocent enough, but all the hellish labor, gnashing of teeth, and fits of cursing that go into a simple task like selecting final colors, are invisible to most .. as is the time spent sulking …

That last comment was innocent enough, but all the hellish labor, gnashing of teeth, and fits of cursing that go into a simple task like selecting final colors, are invisible to most .. as is the time spent sulking …

Dyeing is already a place most fear to tread, and the reality of choosing colors for dry flies is an agonizingly long effort.

So I’ll demonstrate my pain by asking, what color is that innocent little swatch featured above?

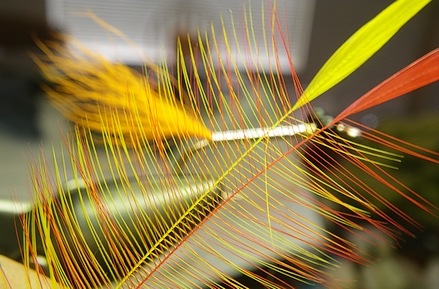

Dyeing materials for dry flies is not the rich and colorful business that is dyeing hackles for steelhead or big chunks of polar bear for streamers, rather colorations used for dry flies are typically pastel, a weak shade of color, not the lemon-yellow, orange-orange of your favorite breakfast cereal …

Instead you take an intentionally weak helping of color and dilute it so the colors are suitable for dry fly bodies; the pale olives, rusts, yellows, and grays, that make up your go-to colors.

“Weakening” is much worse to contemplate, given the many variables that affect bright colors, and how weak colors add more complexity given the many paths to dilution, including; additional water, pulling a material after a short immersion, or overwhelming a fixed amount of color with a large amount of materials.

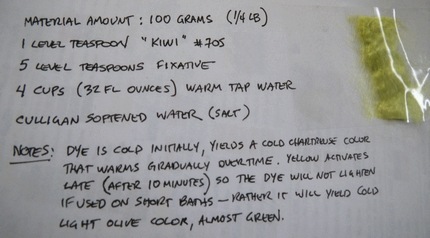

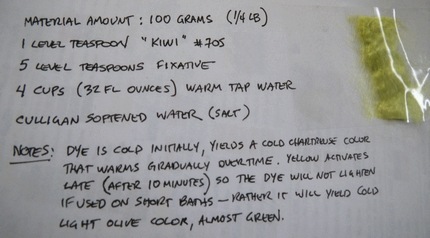

… and while I continue to insist that dyeing fly tying materials is really quite easy, getting the same color a second time is &%#$@# impossible. Sure we write copious notes to record both keeper colors and clean misses, but when waxing lyrical – what exactly did you mean by “toothpaste green?”

Most colors of dye are mixtures of other colors, that when combined in a traditional bath, yield something similar to the label. A complex color like Olive, which contains yellow, green, and black, begs the question – which of the component colors dyes first?

If the black colors first, then yanking the material quickly yields a gray. If either the green (yellow+blue) dyes first – it’ll either be a dirty yellow, or a cold pale green – and if the yellow is first it’s liable to have a hint of either black or green, and will wind up a mustard.

Resolved to buy someone else’s efforts? So, have I …

What’s complicating things is I’ve had my hard water softened compliments of Culligan, and the increased salt in the water has added a new wrinkle to old calculations.

What’s complicating things is I’ve had my hard water softened compliments of Culligan, and the increased salt in the water has added a new wrinkle to old calculations.

Even better is the announcement that well water is no longer fashionable in my town (read toxic) and how they’ll be pumping Sacramento River water in to mix with all the agricultural runoff. The resultant brew will have chemicals added, “to make it smell and taste better.”

Which means all my hard work will have to be redone in 2016, once construction is complete property values decline even more …

Until then, I continue to plunk perfectly good materials into an intentionally weak stew to come up with the twenty or thirty needed to make a good dry fly selection. Then I try to create them a second time the following week, after reading my careful worded notes …

This latest trial was for the Pale Morning Dun color (for the Hat Creek / Fall River drainage of California), and was a miss. The Pale Olive was the correct intensity but it needed a bit more yellow to match the version dyed last week.

Most vendor-created packaged dubbing change a couple shades with every run, they just run big batches that last a couple of seasons to make it less noticeable.

It’s easy enough to save the dull material at left, I’ll add it to a weak yellow bath for a minute or two and it’ll be nearly indistinguishable. It’s one of those hard lessons learned early, “ … that nothing can fix a dye job that’s too dark …”

Which is why after shipping out quite a few samples, I’ve gone silent over my latest brainchild.

Add in work-related travel, a winter that never came, and I’m behind on a great deal of efforts I was counting on completing during those dark, rainy, months between Christmas and Opening Day.

* The swatch above is Olive, yet the yellow component dyes first with only a hint of the black and green, yielding dirty Mustard. Care to try to get that a second time?

Naturally I’d rather not dwell on the fact that I was right and you was horribly wrong … actually I would, but I’d exhaust the subject of my presumed greatness in about three seconds.

Naturally I’d rather not dwell on the fact that I was right and you was horribly wrong … actually I would, but I’d exhaust the subject of my presumed greatness in about three seconds.

While I relish reading about Science, I’ve no doubt that it’s more fun to be interested in Science than to be a scientist. For all the reasons you’d suspect; it’s much easier and more fun to jump to conclusions than prove them, and you can defend your erroneous assumptions by claiming the other fellow is stupid, something the scientific process will not countenance.

While I relish reading about Science, I’ve no doubt that it’s more fun to be interested in Science than to be a scientist. For all the reasons you’d suspect; it’s much easier and more fun to jump to conclusions than prove them, and you can defend your erroneous assumptions by claiming the other fellow is stupid, something the scientific process will not countenance.

Firstly, with all the clothing manufacturers jettisoning olive drab, tan, and the muted tones in favor of shirts, waders, and fishing vests of Marigold, Puce, Cinnamon, and Bubblegum, we’ve got a better uniform than grubby Dakotan Oil frackers …

Firstly, with all the clothing manufacturers jettisoning olive drab, tan, and the muted tones in favor of shirts, waders, and fishing vests of Marigold, Puce, Cinnamon, and Bubblegum, we’ve got a better uniform than grubby Dakotan Oil frackers … That last comment was innocent enough, but all the hellish labor, gnashing of teeth, and fits of cursing that go into a simple task like selecting final colors, are invisible to most .. as is the time spent sulking …

That last comment was innocent enough, but all the hellish labor, gnashing of teeth, and fits of cursing that go into a simple task like selecting final colors, are invisible to most .. as is the time spent sulking … What’s complicating things is I’ve had my hard water softened compliments of Culligan, and the increased salt in the water has added a new wrinkle to old calculations.

What’s complicating things is I’ve had my hard water softened compliments of Culligan, and the increased salt in the water has added a new wrinkle to old calculations.

The Good News is what we’re pissing into the creek isn’t killing fish outright, rather all that runoff from wastewater treatment containing our prescribed anti-anxiety, lowered cholesterol, blood- thinning stimulants, merely make them giggle watching Mom struggle with a faceful of your artificial …

The Good News is what we’re pissing into the creek isn’t killing fish outright, rather all that runoff from wastewater treatment containing our prescribed anti-anxiety, lowered cholesterol, blood- thinning stimulants, merely make them giggle watching Mom struggle with a faceful of your artificial …