Ask anyone who’s ever fiddled with materials and you’ll see the involuntary shudder when Black is mentioned. While it enjoys status of being a must-have color among fly fishermen, getting a good permanent black will drive both professional and hobbyist to tears.

Ask anyone who’s ever fiddled with materials and you’ll see the involuntary shudder when Black is mentioned. While it enjoys status of being a must-have color among fly fishermen, getting a good permanent black will drive both professional and hobbyist to tears.

… and you don’t have to do it yourself to grit your teeth, as most packages of black materials stain fingers, clothing, and skin.

Dye companies have an asterisk next to their black(s), requiring you to double the amount of dye used to achieve a complete deep color. That translates into stained sinks, discolored fingers, and rinsing the material at least three times as much before the water even resembles clear.

Slurps and dribbles are permanent, and the evidence can’t be hidden, as you and the sink are the same color of sepia.

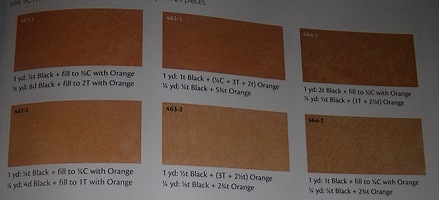

Black is the absence of all color, it can only be approximated by adding dark colors together – and as a result every vendor’s recipe is different.

Black is the absence of all color, it can only be approximated by adding dark colors together – and as a result every vendor’s recipe is different.

Most could be described as warm or cold blacks, as they depend heavily on purple which is a mixture of red and blue. Tossing other colors into purple will raise or lower the red or blue – yielding a warm or cold color.

To further complicate matters is the presence of many colors of black. Black, jet black, carbon black, true black, and even new black, are labels used by dye vendors to distinguish between black-as-night and dark charcoal gray.

They’re all a pain to reproduce and your only certainty is the result will be messy, stain the top half of your torso, and won’t be black enough.

What we think of as black is actually Jet Black, the darkest and deepest of all the vendor variants. Not all vendors call it as such, when presented with a choice, that’s the darkest of all.

Many things can interfere with the coloring process, including natural colors (we assume the black will cover them up), dirt, grease, and oil, and the blend of dye itself. Dyes are made from rare earths and minerals, all of which activate at different times and temperatures – and if the bath doesn’t get hot enough, or is too hot – it’s possible to have a color misfire.

Many things can interfere with the coloring process, including natural colors (we assume the black will cover them up), dirt, grease, and oil, and the blend of dye itself. Dyes are made from rare earths and minerals, all of which activate at different times and temperatures – and if the bath doesn’t get hot enough, or is too hot – it’s possible to have a color misfire.

The rinse water at left shows you how visuals cannot be trusted. Rinsing a pound of loose fur in dish detergent yielded a great deal more dirt than we suspected. It also shows why scissors grow dull, not only will the dirt prevent color from setting on the material, but this kind of grit is hell on the sharpest of scissors.

Familiarity with your dye vendor is the only way to know whether your result has been influenced by other agents. Dyeing six or seven batches of material will commit the shade to memory, allowing you to fiddle with heat and quantity if you get something unexpected.

Over dyeing the material a second time, with partial drying in between can usually fix a poor initial attempt, but sometimes it’s the material itself that resists coloration.

Guard hairs and stiff shiny materials are quite hard compared to loose fur or marabou. A rich deep black in Marabou may not be the same shade when dyeing a slab of Polar Bear, or similar tough material. Over dyeing a second time may fix a dark gray, and it may be enough to over dye it with a deep purple, or dark brown, rather than black.

Guard hairs and stiff shiny materials are quite hard compared to loose fur or marabou. A rich deep black in Marabou may not be the same shade when dyeing a slab of Polar Bear, or similar tough material. Over dyeing a second time may fix a dark gray, and it may be enough to over dye it with a deep purple, or dark brown, rather than black.

At left is about seven pounds of loose fur (multiple animals), how many “blacks” do you see?

Only the foreground two were listed as Jet Black (left) and True Black (right). The rearmost is Gunmetal Gray, Purple in the center, and the rightmost dark color is Silver Gray. The True Black (right foreground) has been dyed twice with twice the amount of dye as normal, yet is still a close match to both Gunmetal and Silver Gray. This shows why familiarity with the vendor is so important – the labeled color is of little help.

Outdoor light adds a bit of blue to the bucket of True Black. The Jet Black on the mound of drying material shows little change from indoor lighting, it’s still the darkest black in any condition.

For my use the current color of the True Black will work just fine, it’s a component of a larger batch of dubbing that will be a dark gray.

While it showed red in the drain (see above picture) once on the material and exposed outdoors it shows blue, suggesting that if I wish to darken it further I would over dye it with a dark brown – as the red of the brown would cancel the bluish tint shown in the photo.

The rest of the table is yellow that was fast dipped in orange, and then soaked in a weak olive, just one of many secrets to my Golden Stone mix.

I mention it only because my porcelain dye pot sprung a leak while cooking three pounds of hair. Yellow being the most forgiving color and dyeing even in lukewarm water, once I heard the burner sputter – I had time to jam my hand into the pot and cover the hole without parboiling them precious fly tier fingers …

… jaundiced to the elbow is easy for us brown water types to explain.

Test Jet Black, True Black, dyeing hair, bulk fly tying materials, dubbing, Golden Stone, fly fishing, fly tier, acid dyes, protein dyes

The only way I can figure it is there must be two demographics for fly fishermen; the starry eyed fellow that approaches the counter with an eight hundred dollar rod and asks, “what else do I need?”

The only way I can figure it is there must be two demographics for fly fishermen; the starry eyed fellow that approaches the counter with an eight hundred dollar rod and asks, “what else do I need?”

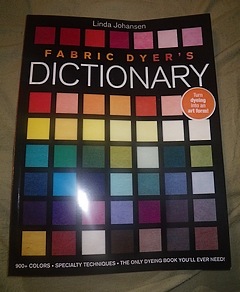

Wet dyeing is a mixture of chance and things we can bend to our will, “dry dyeing” allows us to micro-manage color and turn lemons into lemonade.

Wet dyeing is a mixture of chance and things we can bend to our will, “dry dyeing” allows us to micro-manage color and turn lemons into lemonade.

Call me a slow learner, but the aerial display of the fourth will have nothing on the fireworks tonight …

Call me a slow learner, but the aerial display of the fourth will have nothing on the fireworks tonight …

As no points are scored for being banned from the kitchen, it’s important that the how to make a complete mess is tempered with how to extricate yourself from a screaming and angry woman.

As no points are scored for being banned from the kitchen, it’s important that the how to make a complete mess is tempered with how to extricate yourself from a screaming and angry woman. At right is the Righter of Kitchen Wrongs, cleanses fingerprints, restores the Pristine to the porcelain, and is capable of making you innocent of all imagined crimes.

At right is the Righter of Kitchen Wrongs, cleanses fingerprints, restores the Pristine to the porcelain, and is capable of making you innocent of all imagined crimes.

The next time someone mentions fly tying you can print the picture at left and insist that rehab is more than you can bear…

The next time someone mentions fly tying you can print the picture at left and insist that rehab is more than you can bear…

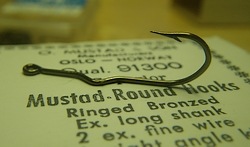

Mustad 91300 – Superb fine wire Bass Popper hook, with no takers due to the zig zag in the shank. The eBAY audience either doesn’t recognize what to do with it, or doesn’t fish Bass – and you get 500 for $0.99.

Mustad 91300 – Superb fine wire Bass Popper hook, with no takers due to the zig zag in the shank. The eBAY audience either doesn’t recognize what to do with it, or doesn’t fish Bass – and you get 500 for $0.99.

The crowd is wise to the Mustad 9143 Dry Fly hook now – but not before I scored a couple thousand for $0.99 per thousand. Offered in the thousand-pack in size 16, and in boxes for size 18 and 20.

The crowd is wise to the Mustad 9143 Dry Fly hook now – but not before I scored a couple thousand for $0.99 per thousand. Offered in the thousand-pack in size 16, and in boxes for size 18 and 20.

There’s not too many sizes left of the Mustad 3116A, but there are plenty of size 9 and size 2 left. This was my favorite, 2X strong, down eye, Limerick bend, short shank, equipped with needles for points. Absolutely bestial sharpness. All of my Shad flies are being swapped to this iron immediately. Good strong steelhead and salmon hook, strong enough for big Carp – and was available in all the even and odd sizes until I saw them.

There’s not too many sizes left of the Mustad 3116A, but there are plenty of size 9 and size 2 left. This was my favorite, 2X strong, down eye, Limerick bend, short shank, equipped with needles for points. Absolutely bestial sharpness. All of my Shad flies are being swapped to this iron immediately. Good strong steelhead and salmon hook, strong enough for big Carp – and was available in all the even and odd sizes until I saw them.

Looking at all those little packs of dubbing and gauging capacity were I to wad them into a single container. Nearby are the zip loc bags groaning under the stress of a couple ounces of custom dyed, blended, or curried fur …

Looking at all those little packs of dubbing and gauging capacity were I to wad them into a single container. Nearby are the zip loc bags groaning under the stress of a couple ounces of custom dyed, blended, or curried fur …