I have it on good faith that the only reason they wanted the prime saddles for hair extensions is because we put, “No Gurlz Allowed” on the clubhouse door …

That’s the last of it honest, we can have the rest.

I have it on good faith that the only reason they wanted the prime saddles for hair extensions is because we put, “No Gurlz Allowed” on the clubhouse door …

That’s the last of it honest, we can have the rest.

Those of you old enough to remember Dan White and the Twinkie Defense are about to make bank, but only if you can hold a straight face while being pummeled by Gendarmes and hairless screaming females …

Those of you old enough to remember Dan White and the Twinkie Defense are about to make bank, but only if you can hold a straight face while being pummeled by Gendarmes and hairless screaming females …

No, we’re not interested in a mundane purse snatching, we’re about to score acres of free 12 – 15 inch saddle hackles that we can turn around for obscene profits on eBay.

US citizen Edwin Rist, 22, who admitted burglary and money-laundering at a previous hearing, was described as a James Bond fantasist by his solicitor.

St Albans Crown Court heard he acted on his “obsessive interest in birds”.

The court was told that Rist suffers from Asperger’s syndrome. His prison sentence was suspended for two years.

Our museum loving “poor little rich boy” has evaded jail time despite stealing 300 pelts from a priceless collection and then parting them out to his buddies overseas (to the tune of about $30,000). It appears the jury bought the tale of misspent youth, video games, and James Bond, which along with Pop Tarts, coerced the lad into a lifetime of antisocial behavior with a hard on for Macaw …

That’s okay, for Dan White it was Twinkies and Coke that made him blow daylight through Mayor Moscone, Harvey Milk, and anyone else that got in his way.

Now that we recognize that I’m showing the symptoms of “an obsessive interest in birds” – and after a lifetime of watching Wiley Coyote fail to capture the Roadrunner, I’m liable to be set off by the sight of dyed saddles, and grab an entire fistful of hair in one big wrench …

… followed by falling prone, curling into the fetal to protect the jewels, enduring the beating while babbling about pyramids and tin foil.

Leave it to friend Leaping Bluegill to disclose the depths of our despair, how deep that hole is, and how our dry flies will be held hostage over the next couple of decades …

When it was wives and daughters we were bound by the laws of society, now that the enemy is a quadruped all we’ve got to worry about is angering PETA eco-pussies, and absent a life sentence for us patriots, Old Fat Ass won’t know what hit him …

He’ll crack an eye to the sound of the clip slamming home – but once those tracers start skipping off the wainscoting he’ll realize his days of farting on the sofa are gone.

I’ll wait until he hits that turn into the kitchen, when those trimmed toenails start to lose purchase, “skritch-skritching” on the linoleum and momentum requires trading paint with the fridge … flick that selector switch into full auto, put the front blade where he’s gonna be and lean on that trigger hard …

I seen “Old Yeller” and it sucked too. “Best Friend” was what we called you, because we never could remember your real name, you foulsmelling, fleabit, Prick …

Adorable little ruffian with Whiting neck hackles highlighting those dark eyes so fetchingly … We’ll see how well the anchors hold when I chase the little SOB through the dog doody area while four snarling steel belted radials seek to make “Foo Foo” a throw rug.

The Singlebarbed Guide to whether your Dog is worth keeping

1. Less than ten unassisted retrieves of live game last season, the dog is worthless and a potential harbinger of Satan.

2. … a hamburger is neither “live” nor “game”, see #1 above.

We had a chance when it was a fad, now … now it’s personal.

It’s like turning on the living room light to find your dog frozen into immobility as he rearranges that warm dent on your sofa cushion. It’s that same shocked expression that’ll bring a smile to your face as you kick his butt off the soft and fluffy …

It’s like turning on the living room light to find your dog frozen into immobility as he rearranges that warm dent on your sofa cushion. It’s that same shocked expression that’ll bring a smile to your face as you kick his butt off the soft and fluffy …

There’ll be shock and amazement aplenty when all those fly tiers realize the folks pimping Whiting saddle hackle to women for hair extensions is their local fly shop.

Naturally, Whiting promised their first priority will always be fly tiers and fly shops – and the faddish teenyboppers that wanna-look-like-Miley-Cyrus can all go without (meaning they can lightfinger Poppa’s stash) .

So the fly shops pump their fist along with their customers, as it’s a boy’s life and “no gurls allowed …” – even though them counter-men adore all that taught flesh giggling their way through the upstairs dander.

Now that their supply is assured by Whiting, they’re onto eBay by the bucketload, selling dyed Grizzly hair extensions by the fistful. The Whiting shipment received and hustled into the back room where it’s dismembered into little 5 feather packets and sold for $10 – $15 each on ebay…

… giggle …

…while you mean old men have to do without.

What’s not so smart is most of them are selling under the shop account, and was I the Whiting Hackle Company I might want to be bring a couple of those vendors up short, as I have enough troubles keeping the fly tying market in feathers without some sharp SOB hoarding all the good saddles in the back room – claiming them damn girls bought it all ..

What’s not so smart is most of them are selling under the shop account, and was I the Whiting Hackle Company I might want to be bring a couple of those vendors up short, as I have enough troubles keeping the fly tying market in feathers without some sharp SOB hoarding all the good saddles in the back room – claiming them damn girls bought it all ..

Just click the Nomad Anglers picture above to see what they’re telling their customers …

The only reason I’m not completely incensed is because the selfsame idea crossed both our temporal lobe about five minutes ago, and you’re suddenly wishing you’d paid more attention to my articles on dyeing.

… and for those shops poised to unload onto the marketplace, don’t use words like “Cree” or “Furnace” to describe your hackle, hair dressers don’t use words like that, dummy.

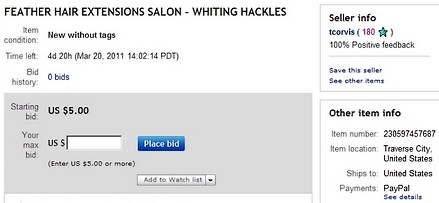

Nor is it surprising that I’d find Orvis selling hair extensions to the gals. The seller above appears to be the Traverse City, Michigan Orvis store, called “Streamside Orvis.”

With Opening Day just over a month away, I’d accuse these shops of really poor timing at the minimum. Nothing like a shortage of hackle just when the customer base seeks it most.

After three or four months you look down at the handkerchief and the sodden remnant of flaming pink raccoon tail you just sneezed up, and your first thought is about the fly tying “15 minute rule” and whether you’re allowed to recover and rebag it once dry …

Thirteen “pillows” of fur isn’t much to show for four months work, given the nearly 20 additional colors completed in theory, yet lack any physical manifestation.

14 actually, I started “Dreamy Mint Julep Caddis Carapace” this morning.

It’s the sum of every rainy weekend, all the frosty winter mornings, evenings after work, and why you should have listened to Poppa when he mentioned college – and how if you were as smart as claimed you’d be using head instead of back …

In the current economic environment, especially since both Tripoli and Wisconsin have fallen to revolutionaries, it’s a bit of a comfort knowing that I won’t be pressed into service as a short order cook, given my second career and the vast potential it holds.

Making little ones from big ones being a cornerstone of the US penal code, so I’ll have plenty of company with a single misstep.

Many of you participated in this experiment, and I owed you an update. Some picked colors and offered feedback, some fiddled with textures, most experimented with it, and at some point it will be available. My initial attempts at automation have failed miserably, so everything above has been made by hand.

Looking at all that dubbing makes me think of Edwin Teller, and the amount of suffering a handful of raccoon’s backside could mean to most of the major watersheds in North America …

… and how easy it’ll be to sleep at night, given the circumstances.

He looked both ways before passing me the baggy, and being as it’s California I didn’t leave it out in the open for prying eyes, quickly tucking the goods into a breast pocket, before returning to the truck whistling innocently.

I might have been less eager if I’d known more about songbirds and whether you’re even allowed to keep one, let alone how many in possession and which warbler gives the electric chair without the luxury of trial.

Once the evidence was tucked into the freezer I did a little unrefined search to determine that I was now in violation of most fish & game legislation, both federal and state, and in addition to tempting fate with my “salvage” of three dead birds, the next knock on the door is liable to be the National Wildlife Service in full body armor.

Your cats can keep killing birds with no threat of legal reprisal. I don’t think that you can be held responsible, unless you have the feathers in possession. A few feathers in your backyard probably won’t get you into trouble. You, however, can’t legally even pick up a feather that incidentally falls off of a protected songbird. If it isn’t a game species, you probably can’t legally keep it. This is what we have to do. First, we need a federal “special purpose salvage” permit from US Fish and Wildlife. This give us the right to pick up dead migratory birds, as the feds have jurisdiction over migratory birds. Second, we need a state salvage permit as all songbirds are protected. In addition, I must keep detailed records as to what is done with every bird that comes into my possession. That is, is it turned into a study skin, disposed of or released. Finally I have to have a federal permit for any federally listed threatened species and another permit for any bald eagles. That means a separate permit for each specimen. Then there is a state permit for all state listed threatened species. What does this mean if you come into possession of contraband material without the above permits? Basically that you should leave it there, or dispose of it.

Assuming I was gifted the alleged animals, and my sense of utilitarian overcame my traditional adherence to the law, besides the five to life without parole, there’s a right way and wrong way of receiving some dripping lifeform your buddy, or circumstances, presents at your door.

First and foremost the legality of the affair, whether game animal or otherwise is always in question. Second, is the amount of time that transpired before that car bumper intersected the flock of dove, and whether you’re on the fresh or odious side of the bell curve.

If the corpse bounces to a stop at your feet, consider toeing it into a bush, given that there is still plenty of livestock on the creature, none of which will be leaving until the body begins to chill. Tomorrow would be much better to collect your booty, given you can bring gloves and a sterile baggy, versus carrying the bleeding SOB in your shirt pocket …

As did my mysterious benefactor, a couple of days in the freezer ensures that everything living on the host isn’t – and pretty much leaves a scentless little ice cube of sparrow, warbler, or linnet, or finch.

One or two is plenty, and given the wonderful soft hackles they possess, you’ll be gripped by this selfsame dilemma at some point. One or two only because most of the bird resembles every other songbird on the planet; a dull drab brownish gray top and a few gaily colored feathers on the breast or near the tail.

In ice cube form a couple of delicate pinches will remove most of the useable – too big a pinch brings the skin with it, which is undesirable as it’ll add moisture and a hint of decay into whatever drawer is utilized. Small pinches will remove only feather – and due to size there’s only about five pinches of feather worth having …

I’d guess these are some form of finch or sparrow, as they have little in the way of color to identify them. As I often wander the owner’s field picking up turkey tails and flight feathers in the fall, my appetite for feathers is well known.

Small birds have small feathers, which is exactly what our traditional materials like Partridge and Grouse lack. Other than using a distribution wrap or something similar to reduce the flue length, soft hackles are often wildly disproportionate to hook size … which isn’t necessarily always a bad thing …

The issue is that small feathers can’t be wound or gripped by hackle pliers, as our hammy fingers lack the finesse to avoid breaking them.

I use them by throwing a quick dubbing loop, inserting the hackle into the loop with my fingers, then spinning the loop to reinforce the stem with thread. As long as the hackle is not tied onto anything, either by its tip or its butt, it will not break.

As the feather spins with the thread it will shorten, which is why neither end can be attached to anything. The feather will spiral about the thread and consume some of its length in those wraps. Two lengths of thread give it a real “stem” and we can attach hackle pliers and wind the hackle (while brushing it backward).

Note how the hackles are in proportion to the hook size. These are not stiff like Partridge fibers, they’re actually so soft and mobile that I’d characterize them as marabou with a hint of spine. Breathing on the fly will make all the hackle move to the far side, making them incredibly lively in the water – more so than the traditional soft hackles.

I’d recommend not using any head cement. Like marabou the fibers will soak any slop instantly, making them much less effective – and ruining the fly.

I guess I’m a bit less notorious with the authorities than the Trout Underground would have you think. In light of my sudden fascination with European Starling and then a mysterious kill of same – with carcasses scattered across most of Sonoma …

I guess I’m a bit less notorious with the authorities than the Trout Underground would have you think. In light of my sudden fascination with European Starling and then a mysterious kill of same – with carcasses scattered across most of Sonoma …

… the county next door that I never visit, ever.

Given a good bit of downhill and a tail wind, a silver Toyota pickup could resemble a big rig, especially when broadside to traffic and host to some idjit flailing around with a butterfly net …

It’s the perfect crime, given the fact they’re an invasive species and the Fish & Game folks wouldn’t flinch if they caught me harvesting them with a Death Ray …

At times I think even PETA hates starlings, universally reviled – it seems even little old ladies consider them cockroaches of the sky …

When I lived in the woods the local rice farmers would pay for your ammo, sending great groups of killers onto the paddies to blow hell out of yellow-hooded and redwing blackbirds. I tried desperately to come up with fly patterns that would allow for an orderly disposal of so many carcasses and failed miserably…

… something about black makes it an absolute must-have – but like licorice, you “must-have” in small doses …

Having re-upped the half dozen skins I keep around, and flush with small, soft black hackle – I’m reminded of all the other uses it was put to back in the day…

Strangely enough outside of using it for black hackle on all forms of sinking flies, mostly I used it as Poor Man’s Jungle Cock …

Most of the hackle feathers on the back and shoulders have a nicely defined yellow tip. Grab a pair of them and slide one down about a quarter inch …

A bit of wax or vinyl head cement (flexible) is all that’s needed to transform a tawdry little bird into something a rich kid that likes flutes is willing to steal for …

A bit of wax or vinyl head cement (flexible) is all that’s needed to transform a tawdry little bird into something a rich kid that likes flutes is willing to steal for …

… knowing where he’s headed we’ll observe a brief moment of solemn knowing his fly tying is bound to suffer in the face of the sudden demand for his flautist skills …

It all started with five years spent on graveyard shift. Sleeping during the day and working all night appealed to me in some odd fashion, mostly I attributed my ease at being the only fellow in 48 floors of offices was all the time spent afield, as the quintessential antisocial fisherman.

It all started with five years spent on graveyard shift. Sleeping during the day and working all night appealed to me in some odd fashion, mostly I attributed my ease at being the only fellow in 48 floors of offices was all the time spent afield, as the quintessential antisocial fisherman.

My co-workers never saw my savage coupling with the leftovers from the office party, didn’t have to watch the thin veneer of civilization stripped away as I stalked loose change in the return mechanism of candy machines that dotted the employee lounge.

A note on my desk and half empty plates left in the fridge was my only interaction with the rest of the planet.

With my metabolism completely corrupted by the odd schedule, I resumed working days with little outward issues. I had to remember to bathe again, and observe the societal pleasantries associated with co-workers that were confirmed humanoid; a nod, a wave, an occasional smile.

… but I never was able to sleep past 0600 ever again. Which is why it’s my habit to buy my groceries on Sunday, while the rest of the planet sleeps blissfully.

… and while the medium has changed, natural materials capable of staining holy hell out of pants and fingers, fur and feather alike – I find myself schmoozing the stock clerk at Raley’s the way I would fly shop staff …

… because I’m staring at that monstrous bin of white onions, with the doubly monstrous bin of red onions as its neighbor, and my voice gets all silky and friendly like, “You guys ever empty that onion bin and sweep out all the husks?” says I, all caring and neighborly.

The problem with natural materials is there’s nobody to ask what’s enough, or how many dye baths will crushed walnuts shells make before I should toss them.

Instead, as I’m the only paying customer in the store at that hour, I look left – look right, and then dig out all the white onion skins while the clerk is busy restocking the orange juice or granola bars.

All the while I’m expecting the firm grip on the shoulder, and the command to ten finger the potatoes, so I can be featured on the front page of the paper all pasty and pale in the hot white light of the overhead fluorescents.

If I play my cards correctly it’ll be me and the bums fighting over dried daisies in the dumpster, but only after I convince the checkout lady that her first impression of me as a vile creep, was a bit wide of the mark …

I was convinced the story behind bead headed flies and their speedy domination of the sport was due to fly tiers who dreaded completing that gracefully tapered head, that final step which revealed their skill set even to the casual observer.

I was convinced the story behind bead headed flies and their speedy domination of the sport was due to fly tiers who dreaded completing that gracefully tapered head, that final step which revealed their skill set even to the casual observer.

Weight has always been problematic for fly fishing. The letter of the law allows you to add as much lead as possible so long as it’s covered up, the rest of us especially those without ethics or refined breeding add a big shiny goober-esque bead – elegant in getting the fly down to where fish are, reducing all the discarded split shot us fishermen have been salting the watershed with for the last decade.

We feel bad about the lead / waterfowl thing, but only because of all that wasted flank and oily duck’s arse we can no longer live without. They’ve expired via heavy metal inhalation … accidental versus the double barreled kinetic flavor we had in mind.

Instead the bead phenomenon is considerably larger than all that. The real story is our adoption of the literal and scientific elements of fly fishing being complete. We’ve garnered all the fish killing properties of higher learning, entomology and Latin, and are assured there is no stone left unturned, only a return to the gaily colored attractor flies of yesteryear may provide us with additional challenges.

Ignoring all the mean spirited and literal dialog discussed by the forum crowds; whether a beaded fly is in-fact a fly versus a weighted lure, and the passions that conversation awakens, what we can all agree upon is there is no parallel in nature for a 4mm shiny gold bead, and none of the important aquatic food groups are so equipped.

Certainly it assists sinking the fly quickly, but it also adds the same tinsel flash as the traditional wet flies of the 30’s thru 50’s. Ray Bergman and his cohort may have pitched a horrible scene at the prospect of fishing all that weight, but he was fishing over a couple hundred percent more trout (ditto for wilderness) and probably didn’t need to resort to such gimmickry, as there were ample fish in the shallow water.

Fundamental shifts in angling perception tend to hang around for decades. “Matching the Hatch” dominated the last 40 years, attractors before that, and the trends before those are largely lost to us, but “nobility and butterflies” remain, along with the occasional hoary text and odd references to “yellow flye” whose legendary hatches turned the sky of both Tigress and Euphrates, “as darke as nyght.”

Only dry fly fishing remains reasonably intact, the physics of floating a fish hook being unchanged despite iPad’s and Internet, and the drab colors of emerging insects being the sole constant on any aquatic menu.

Gone are the smallish and somber flies of steelhead fishing; the stonefly nymphs and egg imitations abandoned for big water-moving attractors whose garish purples and strung ostrich herl hackles have redefined the pursuit of migratory fisheries.

Coarse fishing and its rise to prominence may have had a small role in this, but it’s more likely that natural had worn itself thin due to age and numerous shortcomings. Big beaded colorful flies seduces all the common warm water species, and even the uncommon ones we encountered in urban settings, giving us twice the reason to add a boxful to our vest. Inevitably we found the box while searching for a solution for fussy trout, and despite our fearful glance skyward, no lightning bolt spat from the Heavens as proof that a vengeful Schweibert had been awakened from a dusty grave.

The physical gear followed close on the heels of our new appreciation for color. Puce rods feature Day-Glo backing, shiny gold reels, and anglers boldly announcing their presence with authority, with liberal application light refracting gadgets and Miami Vice pastels to assist us in blending into the surrounding underbrush and its shadows.

Our fly tying materials underwent similar change. Opalescent being the dominant new material of the last decade, showing itself in dubbing, tinsel, and sheet – all of which were eagerly incorporated into contemporary patterns of both fresh and salt. “Sparkles” are in, and both packaged dubbing and artificial hair vie to outshine each other with gaudy light refractive qualities, often as their only real attribute.

Us fly fishermen typically fixate on a prophet to attribute our 180 degree about face of conventional wisdom, some new Oracle of angling that we can toast at speaking engagements, delights in upending all we’ve held sacred, and commands those heady comps of the swank remote lodge cartel.

Schweibert had his 15 minutes, as did LaFontaine and sparkle yarn, now it’s the rebirth of the attractor – forged in the steely cauldron of the former Eastern Bloc, and returned to prominence with long rods, rainbow hued Czech nymphs, and the two fly cast, proving that which is ancient can be expensive again …