It’s the only part of the fly that works entirely against you, whose real value is the spot of color it leaves when closing the gap between tail and wing. It absorbs water, resists drying, and if ever there was a case for “less is more” this is it.

Dry fly dubbing is comparatively humdrum when compared to the litany of clever things that can be incorporated into nymph dubbing. We don’t get to play with special effects, loft or spike, and the only texture that’s helpful is soft and cloying, aiding us in wrapping it around thread.

As the fly derives so little benefit from its presence, other than the hint of color, and as it’s more hindrance than asset, we should apply a bit more science to its selection than merely whether it makes a durable rug yarn.

As beginners we were introduced to fly tying with the natural furs available from Mother Nature. We tried everything from cheap rabbit to rarified mink, and while we could appreciate the qualities we were told to look for, none of the shops carried them in anything other than natural.

There might have been three or four colors of dyed Hare’s Mask, but everything else on the shelves were the miniscule packets of synthetic dander – not the aquatic mammals mentioned in every book about dry flies written in the last half century.

Shops don’t dye materials anymore, and jobbers don’t dye real fur – as synthetic fiber is sold for pennies to the pound – and it’s shiny, which appears to be the only requirement that matters much. Real fur is expensive, has to be cut, attracts moths, and doesn’t come in pink …

When closing that gap between tail and wing, “shiny” doesn’t make our radar much, floatation does, as will fineness of fiber, flue length, texture, and color. It’s the second most common reason for fly frustration, either grabbing too much, or reaching for something ill suited to make a delicate dry fly body.

Floatation being the most desirable given our fly is cast and fished on the surface. Fineness of fiber results in a soft texture that’s easy to apply to thread, and fiber length allows us to plan how big an area of a “loaded” thread we’ll make – sizing the fur to the hook shank, ensuring we’re not needlessly causing ourselves grief when tying smaller flies.

Given that a #16 seems to be the most common size of dry fly on my waters, as it was the most common size ordered during my commercial tying days, sizing dry fly dubbing for a #16 would make my tying much easier.

That extra bit of tearing or trimming could consume 20-30 seconds, especially if you’re looking for scissors, making it one of many shortcuts that could trim minutes off a fly, enhancing whatever miniscule profits are to be had from commercial tying.

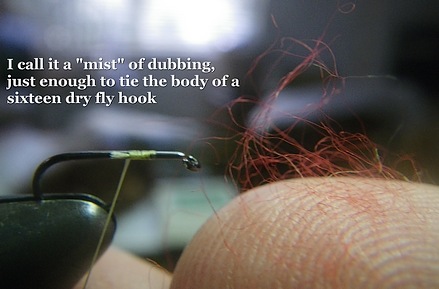

“Sizing” the dry fly dubbing to the hook shank is done by testing different fiber lengths, and determining which length yields the minimum necessary to make a complete #16 body.

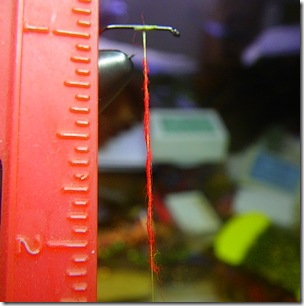

Assume you have a typical synthetic dubbing like Wapsi’s “Antron”, which has a flue length of just over 2.5” . If you decant a tiny bit and all two and a half inches of the fiber were wrapped with concentric turns onto a thread, what size hook would it be the body for?

Hint: a lot bigger than you think …

We can’t wrap the fibers on top of one another as it would make the dubbing too thick and would add to the moisture absorbed. We don’t want fibers too long – requiring us to snip or tear it off the thread, and it’ll burn time as we doctor the shorn area to lock it down. Extra turns of thread and time are also our enemy, making our experimentations with fiber length and the optimal thread load valuable.

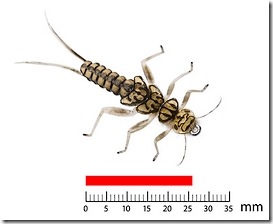

If you think back to those same aquatic mammals that were our introduction to dry fly dubbing, only the beaver had fibers that might’ve been longer than an inch, the balance of those animals; mink, muskrat, and otter, are all short haired critters.

Transferring that knowledge to flue length, suggests somewhere between 1/2” and 1 1/2” should give us similar handling qualities of the aquatic mammals, assuming our materials share their tiny filament width and softness.

Above is that “too small” mist of 1” fibers rendered onto thread. Spun tightly, it renders nearly an inch of body material.

Swapping the 1” fibers for 1/2” only decreased the amount of material slightly, perhaps a 1/4” less at most.

Predictably, our longer fibered Wapsi “Antron” dubbing with its 2.5” flue length covers much more thread, and despite the small diameter of its fibers, shows its unruly nature in the thickness of the noodle it makes.

After a half dozen turns, the remainder of the above will have to be pulled off the thread and removed. Given that implies more than half of what you grabbed, isn’t that a horrible waste?

From the above picture I’d make the claim that Wapsi doesn’t market this product as a dry fly dubbing (the label mentions only dubbing). The fly shop this was purchased at had a wall full of Antron colors, and outside of some Ice Dub and a few strips of natural fur, had standardized on this product for both nymphs and dries.

What actually may have happened is that they were tired of stocking 18 different flavors of stuff that didn’t sell all that well, and reduced the collection to a single flavor – because it’s all the same right?

Wrong, and I doubt your shop manager ties flies at all.

I’m still fiddling with fibers, colors and blends, but am almost done on the flue length tests. I’ve got a natural fiber that’s as fine as an aquatic mammal – which plays hell with blenders, but I’ve got that solved. Now all that’s left is blending of colors and dyeing – and an entreaty to those that want to field test at my expense.

Until then – and using the above photos as a reference, you can eye your local shops offering to measure what fiber length their products provide. Now that you understand that flue length is directly proportional to the amount of thread covered, you can more easily understand why you’ve consistently have more fur than you need, and how you can take a pair of scissors to the package to shorten the fibers to a more useful size.

We’ve been in a synthetic rut for the most part of a decade. Vendors are often lazy and package their materials in whatever form is easiest, often the way they receive the product, not what form makes the best fly or tightest noodle on the thread.

Scissors or a hint of natural fur added to a synthetic can tame its rug yarn roots, making it much more useful than it exists when pulled from the rack.

As part of my latest

As part of my latest  At some point we all flirt with the individual fibers, knotted legs, and artificial or synthetic everything – mostly because the flies look much too delicious to ignore…

At some point we all flirt with the individual fibers, knotted legs, and artificial or synthetic everything – mostly because the flies look much too delicious to ignore…

It was so much easier when I lived on the banks of Hat Creek and could fiddle with the fly before throwing it at the same fish I’d thrown it at the night before. If they ate it, it was success. If they didn’t, we kept fiddling with it.

It was so much easier when I lived on the banks of Hat Creek and could fiddle with the fly before throwing it at the same fish I’d thrown it at the night before. If they ate it, it was success. If they didn’t, we kept fiddling with it.