While much of the struggle involves spelling the damn word correctly, the remainder of my frustration is having to refine the fly tying equivalent of , “less is more.”

Fly tying being the art of “taming cowlicks”, wherein us tiers deploy spittle, cement, and thread to lash as much as possible onto the hook, and anything we can’t dominate with finger pressure or more thread gets trimmed away…

… yet, I’m on the converse of that road, attempting to invent transparent by adding materials versus subtracting them, and it’s an unmistakable sign the idea was sound but the execution is likely flawed.

Much of what the local bass are eating are minnows. Observation of what few I could see near shore suggest there is a mixture of opaque and diaphanous qualities to the fish. As most of my traditional minnow styles are not working, despite my best attempts at matching colors and sizes, suggests something else might be the issue.

I’ve been fiddling with colors and visibility, but to date that has been fruitless. A few fish follow the imitations, but none have taken the fly. Contrasting the gaudy strumpet I am towing through the water with the natural suggests I need tone down both glitter and bulk.

Bulk is not easy to remove, given how water tends to flatten and streamline dry materials, and lightening bulk typically results in diminishing the profile of the fly – making it more like a pencil In the water than the traditional “pumpkinseed” minnow shape.

While struggling with a lot of other issues I did manage to come up with an elegant solution allowing me to remove bulk without sacrificing the fly shape.

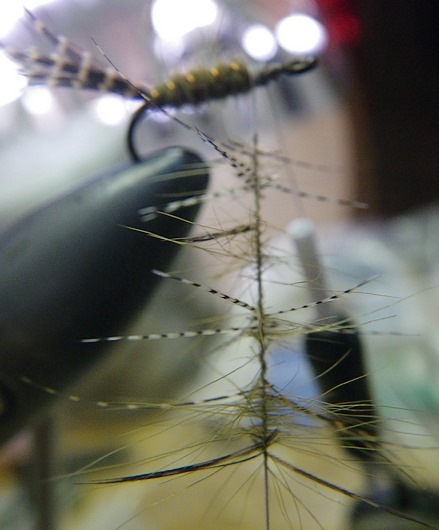

Using a #4 kirbed (point offset) streamer hook, I built a small bulwark of chenille halfway down the shank, after first sliding on a small brass cone.

After whip finishing and adding a drop of cement behind the cone, I retied the thread onto the front of the shank to add a bit of ribbon yarn. I picked a light pink to correspond to gill coloration, and took a couple wraps of the material in front of the cone. The brass cone flared the material further adding a more pronounced 3-D cone shape to the fly.

This “spread” effect of the underbody will cause any material added onto the fly to spread further, giving the proper silhouette without relying on bulky materials for form.

Taking about 35-40 strands of white marabou – I spread them out along a “dubbed loop” – with about 3/4” of the butts on one side of the loop, and the remaining tapered tips on the other. When spun, the butts (with their thicker stem) add bulk to the area containing the pink ribbon yarn, and the less numerous tips add a bit of color behind the fly, without adding opaqueness.

Add three strands of original holographic green flashabou to the top of the “marabou hackle”, and then add about 20 strands of gray marabou in a clump onto the top of the fly. The gray marabou should be about 1/2” longer than the white, and the flashabou should be the longest of all, just peeking out from the other mats to make an enticing flash behind the fly.

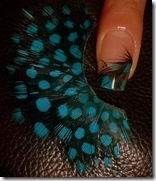

Add five strands of a Montana Fly barred Ostrich plume (sexy looking but nosebleed expensive @ $9.00), to the top of the fly to add a bit of coloration.

The result is an amorphous lump of materials that will lose opacity when dampened. The bulky area around the bead will retain its mass and color akin to the real baitfish – but the nether underbelly will vanish as the grey marabou, tinsel, and ostrich is longer than the white, making it appear diaphanous and transparent.

The final effect when wet is light and airy with the bulk up front. Note that instead of slimming down to nothing the fly retains the all-important minnow shape.

The local fish inhaled it with great gusto this weekend, but the unsavory brutes that haunt the local creek would have been just as eager to inhale the twist-off cap from a Budweiser … so additional research is needed.

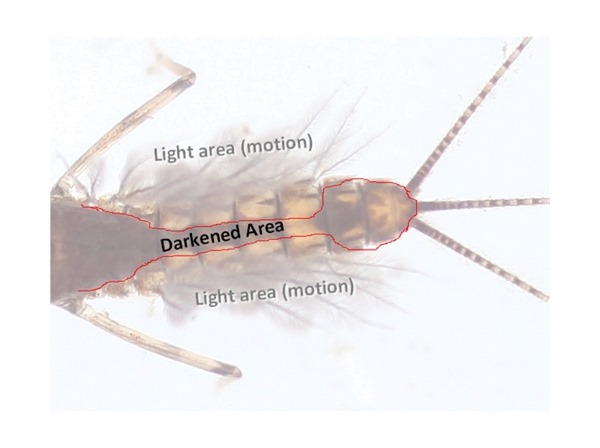

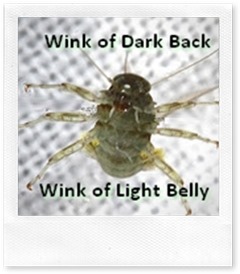

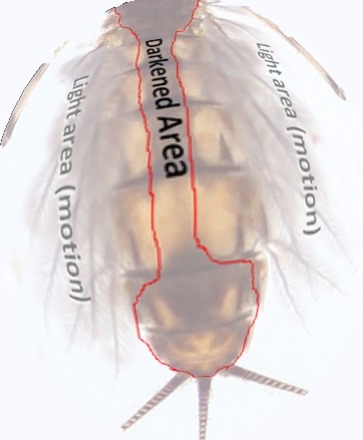

In moving water most fish face upstream. Insects dislodged due to mishap or swimming to the surface come downstream (roughly) head first. Fish on the prowl for targets likely don’t see anything of the abdomen patterning save the wink of dark top or light belly, and only if the insect is swimming in its customary violent tail-centric, up-down, fashion.

In moving water most fish face upstream. Insects dislodged due to mishap or swimming to the surface come downstream (roughly) head first. Fish on the prowl for targets likely don’t see anything of the abdomen patterning save the wink of dark top or light belly, and only if the insect is swimming in its customary violent tail-centric, up-down, fashion.

It was a two room apartment, with four occupants and at least three outdoor hobbies participating. Keeping all those vocations in their respective corners was bad enough, not counting us kids fighting for extra flat space at the kitchen table.

It was a two room apartment, with four occupants and at least three outdoor hobbies participating. Keeping all those vocations in their respective corners was bad enough, not counting us kids fighting for extra flat space at the kitchen table. The folks at

The folks at  “Dubbed Loops” have shown a bit of a resurgence of late, and have always worked well converting hair and fur into hackle for big nymphs. Less well documented is their ability to mix a variety of materials into a single strand, and with a judicious stroke of scissors, can offer new opportunities for feathers that are too big for normal attachment and winding.

“Dubbed Loops” have shown a bit of a resurgence of late, and have always worked well converting hair and fur into hackle for big nymphs. Less well documented is their ability to mix a variety of materials into a single strand, and with a judicious stroke of scissors, can offer new opportunities for feathers that are too big for normal attachment and winding.

I’ll attempt to persuade the materials to clump on one side with finger pressure or saliva, but as the materials have been spun like a rubber band, they will resist your efforts to tame them.

I’ll attempt to persuade the materials to clump on one side with finger pressure or saliva, but as the materials have been spun like a rubber band, they will resist your efforts to tame them.