As we mentioned in Parts 1 & 2, the measure of true fly beauty is held by fish not humans. Unfortunately only averaging 9 days afield your flies are viewed most by people, and suffering their continual criticisms can make a fly tyer resign himself to please both anglers and quarry.

… and in the doing, gain the precision to make his flies sturdier.

We’re down to the final three, each so hideous and daunting as to cause fly tiers to scream, gnash teeth, or give up the craft entirely. Three crucial steps that professional tiers do subconsciously, that plague beginners for decades, are rarely mentioned, and completed so quickly you’ll miss it on a video or live demonstration because you’re drawn to more glamorous materials and technique.

Watching a talented tier can be mesmerizing. A crowd of fellows inching forward looking at some vindictive SOB who’s just palmed a couple ounces of yard-long #16 saddle hackle in Coral Pink. You’re trying to stammer the question, “… Wh … where’d you get that?” – and you miss a half dozen gems of technique while he pretends he’s got a closet full of the material and doesn’t.

Here’s what you missed:

In prior posts we mentioned the difficulty of keeping materials from moving around the shank – either via thread torque, bulk, or method of attachment.

In prior posts we mentioned the difficulty of keeping materials from moving around the shank – either via thread torque, bulk, or method of attachment.

I’ll ask a simple question;

Which holds the tail of a nymph onto the shank, the six turns of thread you used to tie it on, or the forty turns of thread that come with adding ribbing, body, and all remaining steps?

Light bulb.

Thread management is part art form and part physics. Thread is your enemy and we use it as sparingly as is possible. It’s heavy, lifeless, and is always applied in great quantities where it’s least useful.

A tail isn’t “lashed” onto a hook with tight concentric turns, it doesn’t require taming where all traces of it are buried under thread, it’s anchored with three tight consecutive turns of thread at the tie-in point, and then the thread is spiraled to the next step.

That’s true of wings, wingcases, ribbing, bead chain eyes … and everything else.

The anchor wraps occur at the last portion of shank before the fibers become tail. The butt ends will be bound securely by the thread used to dub the body and attach the ribbing, and we don’t need any additional turns to hold them mid-shank. Any tail movement will occur at the anchor point – not in the middle of the fly.

Understanding the physics behind this practice is the hard part, execution is much easier. “Anchor points” exist where the stress will occur – and the thread wraps and tension used are critical only at that spot – all other wraps position the bobbin for the next step.

Less thread pays off in slim profiles, small heads, and buoyant dry flies – and is as memorable to the critiquing angler as is the curves of a Supermodel.

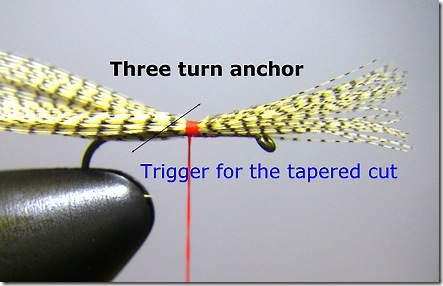

Hand in hand with the notion of “anchor” is the tapered cut. As described above the anchor is needed to hold the material firmly to the shank. Once the three wraps of the anchor are in place, it’s an automatic trigger for the cut.

New tiers are still unfamiliar with everything; small hooks, tiny scissors, unfamiliar materials, and insecure grasp of proportions. They’re thrilled to cut the material at all – and usually after securing it with 46 turns of thread.

Often they’ll “blunt cut” the item, scissors held at right angles to the hook shank so they can square cut the wing or tail butts – leaving a promiscuous gap between material and shank that will have to be addressed by subsequent materials.

Intermediate tiers will have learned the horrors of the lump left by the blunt cut, and will taper their cuts – scissors parallel with the hook shank – cutting downwards at the shank.

… after they’ve secured the item with 26 turns of thread.

A blunt cut can only be used when the material covers the entire body area of the fly.

All that’s needed to attach any part of a fly to the hook shank is three turns of thread.

Bold words, and you’ll note I didn’t say it was attached permanently. If the anchor is the only thread needed to hold the material stationary – and subsequent steps will add more thread to lock down the butts that extend over the body area, than those three anchor turns will hold the material well enough for us to cut the taper – yet will be loose enough so if torque has carried the fibers too far to one side, we can straighten them with finger pressure.

Which is why the Golden Rule applies: Nothing on a fly can be fixed by laying more crap down – because the “three-turn-anchor-tapered-cut” allows us to reposition it before we move to the next step.

We fix as we tie, because we’re learning thread management.

The taper we induce as part of the cut is every bit as important as the anchor and the three-turn trigger cut. For flies that please humans, only two kinds of cut are permitted; the blunt cut when the material covers the entire body area – as in the tail of a dry fly – where it’s trimmed behind the wing, or the tapered cut – which produces the finished body contour.

Using cuts to define body shape is easier than adding the right amount of dubbing to thread to have a thin arse and thicker middle. Beginners and Intermediate tiers haven’t mastered dubbing yet, asking them to be doubly clever in its application will not work.

… and tapered cuts have to be learned anyways – as not all flies have dubbing to make contour. The Quill Gordon is a classic example, it’s body is the stripped quill from a center strand of Peacock eye and the taper of the body is caused by the cuts made on the prior materials.

It’s easiest for a new tier to learn to dub “level” – that’s something he can gauge easily as it’s the same thickness of fur over the length of thread used.

… later, after he finishes digesting the three parts of this post, he’ll be able to master a tapered dub consistently – and will have an additional tool at his disposal.

Nothing gives the prospective fly tyer more trouble than dubbing. It’s deceptively simple, a simple twist between thumb and forefinger – nothing devious or hidden, no wrist motion or hidden timing.

It’s “mash crap on thread” – yet the proper technique of this routine task eludes most tiers for decades.

That’s because there is no technique.

It’s no different than loading a paint brush. A tiny thread, whether it’s waxed or no, can only trap a certain amount of fur tightly. Anything more than that will be trapped loosely – and if you add more will degenerate into a lump of sodden crap that resists your saliva, glue, hammy hands, and everything else you throw at it.

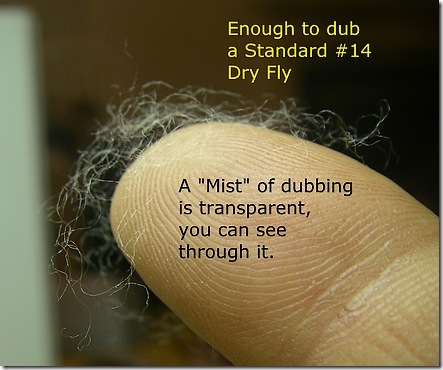

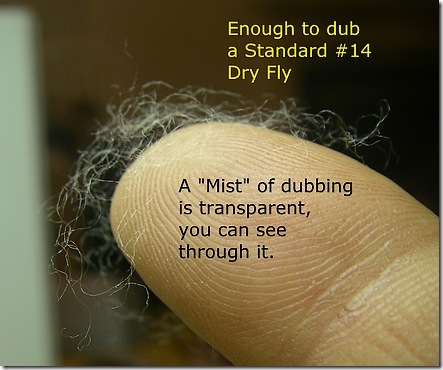

Golden Rule of Dubbing: if you can’t see through it, you’ve got too much.

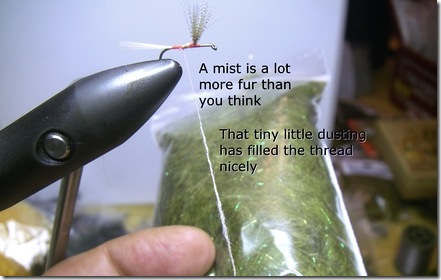

I like to use “mist” to describe the dubbing process to students, as all mists whether water, vapor, or solid, are transparent.

The average #16 dry fly uses so little fur that you could snort it without sneezing … but the gag reflex is horrid.

The inability to apply the correct amount of dubbing, and the myriad of issues it raises, adds a common visual roughness to all your flies – as it’s among the most common tasks performed, and is so very visible.

It will not matter how many videos and demonstrations you’ll watch, the right amount of dubbing is an afterthought to the presenter – he’s mastered dubbing and is busy explaining why you want to fish his Hopper over someone else’s. “Mist” isn’t visible to the camera lens unless it’s within inches of the fly, and much of the action is off screen.

Dubbing can be a very deep subject to us reformed-whore-nutcases, that two percent of fly tiers that go where others fear to tread. We blend fur types and textures, layer colors, give it loft and sparkle, or shape it to replace traditional fly components. But the average tyer still struggles with loading it on the thread, and his Messiah is strict adherence to the Golden Rule of Dubbing above.

Once mastered you’ll realize there are many kinds of dubbing, some are well suited for the task, and others are very poor dubbing choices – but are endured due to the color or sparkle they offer, some quality not found in traditional fur bearers. Baby seal is a great example. A transparent sheath surrounding a white inner core, designed to reflect sunlight away from the animal so it doesn’t burn to death while waiting for that insensitive Canuck to mash its life out with a club.

… sure, you’re all tears now, but that’ll change once someone offers you a nickel bag.

Dubbing that’s suited for dry flies are usually the waterborne mammals, fine filaments and soft to the touch. Nymph dubbing can range from fine to coarse, often contains a goodly component of guard hair, and may contain synthetics to offer sparkle or other qualities.

Just because it’s the right color doesn’t mean it’s the proper tool for the job. Store bought dubbing is simplistic generalist dubbing, not the premier designed-for-dry-flies that us nutcases are fond of …

Putting it all Together:

Let’s put these hideous lessons together in an assault on the traditional Catskill dry, a magnet for criticism whose light coloration shows every lump, knot, and tear stain:

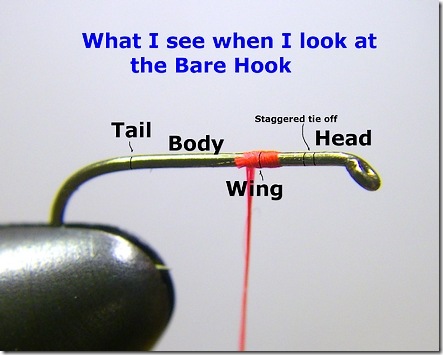

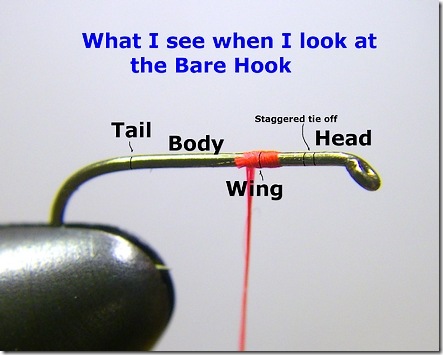

Light Cahill 1: What I see that you don’t

I can’t help it, I see all the tie-in and tie-off points, where I’m going to put the wings, tie everything off, start the head, where the body ends, the entire fly just by looking at the hook shank.

With this “tie by the numbers” approach coupled with thread management, I know when I’ve strayed over a boundary line – and correct it right then, rather than let the problem slowly compound.

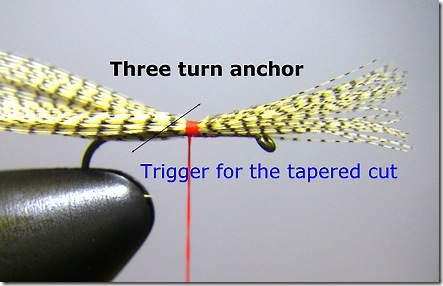

Light Cahill 2: Three turn anchor, trigger for the tapered cut

I’ve attached the Woodduck with three turns of 6/0 Danville. I’ve tied them in about two turns of thread past the mark where I want the wings to stand – this space will be consumed by me folding the material upright, something that most beginner and intermediate tiers forget. Transitioning anything from horizontal to vertical will consume space on the hook shank – and if the heads of your dry flies are perennially crowded, you may be forgetting that critical physics lesson.

Three turns is my trigger for the tapered cut. I’ll come in from the wing side and cut downwards towards the shank. If you have tungsten tipped scissors, it’s the most dangerous cut possible, as tungsten is extremely brittle and you can chip or remove the points if you catch the hook shank in your cut.

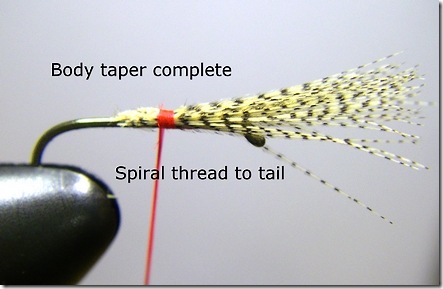

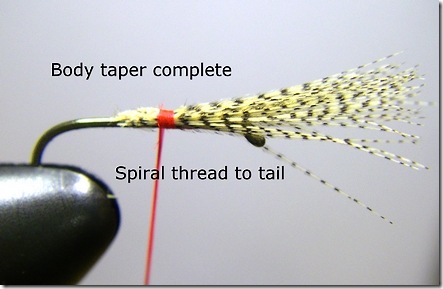

Light Cahill 3: Body taper complete

The tapered cut is complete and my body taper established. The anchor point holds the materials firmly so I’ll spiral the thread to the tail position and mount the tail now.

Note: Us old geezers that used Nymo thread in the 70’s and 80’s recognize that nylon thread can be used in two manners. Spinning the bobbin will essentially turn the filament flat (which is why my thread appears so wide) and will create less bulk than a normal strand of 6/0. Spinning the bobbin again will restore the spun flat fiber to round – best used for the anchor wraps themselves as they can bite into the material.

It’s all part of the art of thread management. Thread is a lot more than it seems…

Light Cahill 4: Tail anchor

There’s a lot to see in this picture, as this is where a lot of techniques start to pay off.

The thread has been spiraled from the wing anchor to the tail mount point. The tail has been mounted on my side (thread torque) with a three turn anchor. The tips of the tail have had a blunt cut (scissors at right angles to the hook shank) but are long enough to traverse the entire body of the fly.

A blunt cut can only be used when the material covers the entire body area of the fly.

… so we have adhered to the rule as stated above … and now we’ll begin to see the reward.

Light Cahill 5: Token Blurry Picture

Because the tail butts are uniform thickness and cover the entire body, the taper induced by our scissor cut has been preserved.

Note the spirals of thread as it was moved from tail mount to the base of the wing. That’s not 56 turns of thread, or even 24 – it’s exactly three. Also notice the tail as compared to the picture above; we’ve only wrapped three turns of thread since the anchor, but note how far towards top-dead-center the thread torque has moved it.

I’ve lifted the wings (consuming some horizontal shank) and divided them, the tie-off and head area remain untouched.

Light Cahill 6: A Mist of dubbing

A mist of dubbing is transparent and even at its thickest point you can see right through it. It will lock onto thread like a fat kid on a candy bar, it will do anything you ask it without complaint, with little coaxing.

Your dry flies will be buoyant and float twice as long as there is so little water absorption, and they’ll dry with a flick or two of the rod. Beauty, with good physical properties to back your play.

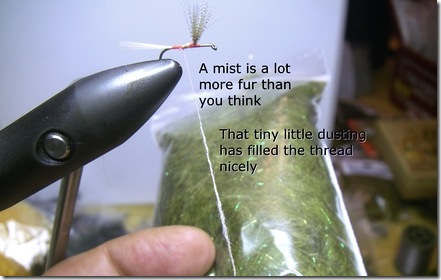

Light Cahill 7: A mist on thread

That’s the same small dusting you saw on Step 7 above. It doesn’t look so small anymore. I’ve switched to tan thread (which is what I use on the Light Cahill) so the thread color won’t overwhelm the dubbing I’ve added.

Note the tail, it is now top-dead-center … bloody miraculous.

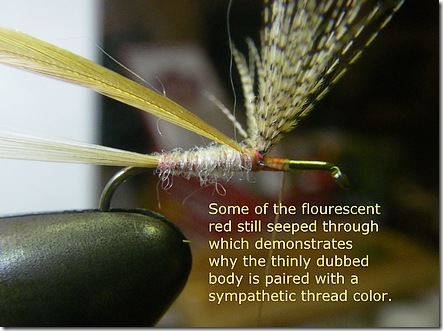

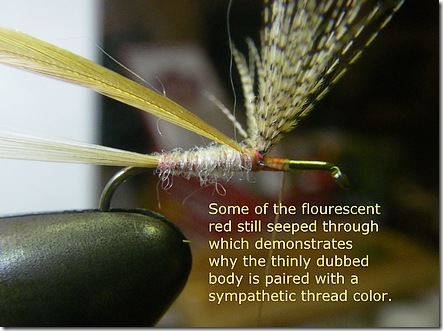

Light Cahill 8: The final dubbed body

A bit of the tail anchor florescence has peaked through – partly because of my reluctance to cover absolutely all of it with tan thread. Thread is always your enemy even when you’re demonstrating what not to do.

The staggered tie off area and head are untouched. I’ll put 1/3 of the hackle behind the wing, 2/3rd’s in front. It’ll be “westernized” – we use a bit more hackle than our eastern brethren due to the brawling nature of our rivers.

Light Cahill 9: Tie off

The hackle has been applied and the reserved area for tieing off the final materials has been intruded upon. The head, which we planned since the bare hook shank, has its area yet untouched.

Light Cahill 10: The finished “westernized” Light Cahill

The finished Light Cahill using most of the lessons we’ve described in the past three posts. This magnified version shows all my foibles – which I’ll gladly admit to while pretending I didn’t see you add it to your fly box.

I’ll do better on the next hundred dozen, honest.

Tags: Light Cahill, Catskill dry fly, small tapered head, fly tying tips, thread anchor, dubbing, tapered cut, tungsten fly tying scissors, beauty as perceived by anglers, fly box, hackle, vindictive fly tyer

The Underwear River Caddis marries the soft hackle and fur collar to traditional shad orange, it’s an homage to classic shad colors with a bit of trout food chaser.

The Underwear River Caddis marries the soft hackle and fur collar to traditional shad orange, it’s an homage to classic shad colors with a bit of trout food chaser. … and for the minnow crowd we assumed a bit of shiny mixed with a lean silhouette would cover all the possible fry that might stumble into a pod of ravenous herring.

… and for the minnow crowd we assumed a bit of shiny mixed with a lean silhouette would cover all the possible fry that might stumble into a pod of ravenous herring.

I’m minding my own business and

I’m minding my own business and

The Royal Coachman Nymph, and I invented it

The Royal Coachman Nymph, and I invented it

In prior posts we mentioned the difficulty of keeping materials from moving around the shank – either via thread torque, bulk, or method of attachment.

In prior posts we mentioned the difficulty of keeping materials from moving around the shank – either via thread torque, bulk, or method of attachment.