I know where they’re trying to push us, and while I have my share of suppositions I still don’t know who they are …

I know where they’re trying to push us, and while I have my share of suppositions I still don’t know who they are …

The reviewers who offered their opinions about the scientific merit of our application, however, stressed that it would be more interesting to find out if a sharp object passing through the mouth of a fish would be painful. Clearly recreational fishing was what these scientists wanted to know about, not fish farming.”

Professor Victoria Braithwaite has penned a book entitled, “do fish feel pain?” – describing the experiments and logic that went into her research on trout sensory receptors.

As mentioned in prior posts that skirted this subject, the scientific community hotly debates whether lower life forms have the ability to suffer – as suffering requires a form of consciousness, and areas of the brain, gray matter among others, that many lower organisms lack.

“Whether sentience and consciousness are processes that occur in non-human animals is something that has occupied philosophers and psychologists for decades, and they have yet to agree on an answer.”

… and despite your experiences to the contrary, a trout’s brain is about the size of a pea, a trait shared with both houses of Congress.

This is not a fishing book, nor is it written for the angling community. I’d describe it as science that never had the opportunity to explain itself fully, given the sudden sensationalism fostered by the press and their misuse of the scientific soundbyte. The author notes she was completely unprepared for the attention paid her when the research was released in 2009, and it appears the book was written to moderate some of that media-furor with scientific groundwork.

Ms. Braithwaite describes in detail the step by step methodology and experimentation that brought her team to their conclusion; that fish do feel pain and have the capability to suffer as we humans.

She outlines the constructs that serve as the piscatorial counterparts to human nerves, pathways to the brain, and grey matter, in a lucid and patient manner that allows us non-scientists to follow without feeling the need for definition or additional explanation.

Using mild solutions of vinegar and bee venom, her team injected trace amounts in the lips of fish and showed how trout behave differently than control groups of saline injected fish, and fish that were merely handled and not injected at all. In all this science there are many tidbits for fishermen, as her description of fish handling and how it can alter trout behavior.

“But the trout that had been given bee venom or vinegar continued to show no interest in the food and their gill beat rate stayed above 70 beats a minute even after the second hour passed. Eventually their breathing rate did begin to decline but it didn’t return to the resting level about 50 beats a minute until almost three and a half hours after they had been initially exposed to bee venom or vinegar. And around that time the fish’s motivation to feed began to return.”

To her credit, Professor Braithwaite stays clear of the philosophical implications of her research, but does pose the obvious question numerous times; is this enough to require us to afford fish similar protections enjoyed by chicken, pigs, and cattle, and should industrial harvest methodology be changed to reflect this newfound consciousness?

While most farm animals are slaughtered in great numbers for our collective table, lower forms of life like fish can be harvested without the luxury of a speedy kill, many gasp out their last minutes while sliding across a trawler deck or flash frozen while still gasping …

I enjoyed the read (it’s a short tome, 184 pgs.) and followed the description of science closely. I’m sympathetic to the theory, so little convincing was required. Mother Nature has always been a miracle of efficiency, and it makes sense that whatever flesh and senses prevent me from touching an open flame, would be present in most of her creatures.

Anglers have the smaller issues to wrestle with once we’re shown as insensitive bullies. While the larger picture doesn’t change, will any legislation stemming from the environmental lobby trickle down into our cold little creek?

I’m unmoved by the larger issue, that of fish as sentient entities. I’ve always had great respect for my quarry, and even when fishing for trash fish have never indulged in throwing them onto the bank as a penalty for eating – and always ate what I killed.

The idea that fish fear me is appropriate, as I mean them harm. A sore lip for three or four days, and I’ll trade wisdom for the experience. It’s part of my birthright as a member of the highest order of the food chain, and while I recognize it as a fortunate happenstance – will spend no time bemoaning the unfairness of it all. My appetites are well documented and unchanged and were there 50 fish within casting distance I would want to catch all of them many times.

I don’t seek parity, nor do I believe equilibrium and complete fairness is even desirable. I swim upstream against the current while the shadows of predators darken my path. The unscrupulous hedge fund manager bent on churning my 401K, the crack head that covets my stereo, and the drunken driver oblivious to lane or direction.

I’d simple say, “No. Food doesn’t have rights, and if I can’t explain to a grieving mother why her son died to an Afghan sniper, I’m not obligated to consider the feelings of a rutabaga when I wrestle it from the ground.”

It’ll get it’s turn when radiation and evolution makes it the top of the food chain.

… and If I make it to infirmity I’ll be a wise and fat fish – with a deep and impenetrable lie that confounds predators and their attempts to lay hands on my fair frame.

That’s Darwinism, the poster child of fairness.

Full Disclosure: The book was provided to me free by way of the Oxford Press, via Eccles of Turning over Small Stones.

Tags: Victoria Braithwaite, fish feel pain, bee venom, lower life forms, trout testing, fly fishing,

The true game-fish, of which the trout and salmon are frequently the types, inhabit the fairest regions of nature’s beautiful domain. They drink only from the purest fountains, and subsist upon the choicest food their pellucid streams supply … [It] is self-evident that no fish which inhabit foul or sluggish waters can be ‘game-fish’.’ It is impossible from the very circumstances of their surroundings and associations. They may flash with tinsel and tawdry attire; they may strike with the brute force of a blacksmith, or exhibit the dexterity of a prize fighter, but their low breeding and vulgar manner of eating, betray their grossness.”

The true game-fish, of which the trout and salmon are frequently the types, inhabit the fairest regions of nature’s beautiful domain. They drink only from the purest fountains, and subsist upon the choicest food their pellucid streams supply … [It] is self-evident that no fish which inhabit foul or sluggish waters can be ‘game-fish’.’ It is impossible from the very circumstances of their surroundings and associations. They may flash with tinsel and tawdry attire; they may strike with the brute force of a blacksmith, or exhibit the dexterity of a prize fighter, but their low breeding and vulgar manner of eating, betray their grossness.” Just finished a deep scan of the 293 page

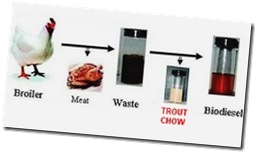

Just finished a deep scan of the 293 page  There are thousands of highly trained scientists examining the diet and feeding habits of both salmon and trout. The Bad News is they’re doing so to determine whether they can be raised on Plutonium pellets, concrete, animal waste, or anything else we don’t want…

There are thousands of highly trained scientists examining the diet and feeding habits of both salmon and trout. The Bad News is they’re doing so to determine whether they can be raised on Plutonium pellets, concrete, animal waste, or anything else we don’t want… Science has upset matchmaking theory and suggested the

Science has upset matchmaking theory and suggested the  The

The

… and year’s later you’re sitting on the side of the bed wearing an antiseptic paper gown – both cheeks exposed (and chilling rapidly), modesty hanging on a strained overhand knot. The doctor pages through your chart, making noises that sound like you screwed up, and turns to you suggesting, “you’ve less than six months to live unless your medical insurer

… and year’s later you’re sitting on the side of the bed wearing an antiseptic paper gown – both cheeks exposed (and chilling rapidly), modesty hanging on a strained overhand knot. The doctor pages through your chart, making noises that sound like you screwed up, and turns to you suggesting, “you’ve less than six months to live unless your medical insurer  I hadn’t thought about it much until I started catching Smallmouth bass with regularity. Trout and saltwater fish shared a similar resigned expression when handled; dull and lifeless – as if garnished with lemon was better than cavorting with mayflies or seaweed.

I hadn’t thought about it much until I started catching Smallmouth bass with regularity. Trout and saltwater fish shared a similar resigned expression when handled; dull and lifeless – as if garnished with lemon was better than cavorting with mayflies or seaweed.