The true game-fish, of which the trout and salmon are frequently the types, inhabit the fairest regions of nature’s beautiful domain. They drink only from the purest fountains, and subsist upon the choicest food their pellucid streams supply … [It] is self-evident that no fish which inhabit foul or sluggish waters can be ‘game-fish’.’ It is impossible from the very circumstances of their surroundings and associations. They may flash with tinsel and tawdry attire; they may strike with the brute force of a blacksmith, or exhibit the dexterity of a prize fighter, but their low breeding and vulgar manner of eating, betray their grossness.”

The true game-fish, of which the trout and salmon are frequently the types, inhabit the fairest regions of nature’s beautiful domain. They drink only from the purest fountains, and subsist upon the choicest food their pellucid streams supply … [It] is self-evident that no fish which inhabit foul or sluggish waters can be ‘game-fish’.’ It is impossible from the very circumstances of their surroundings and associations. They may flash with tinsel and tawdry attire; they may strike with the brute force of a blacksmith, or exhibit the dexterity of a prize fighter, but their low breeding and vulgar manner of eating, betray their grossness.”

“An Entirely Synthetic Fish” is not a fishing book, rather it’s the chronology of the foibles, accidents, egos, and planned strategies that resulted in the Rainbow being the trout of choice for the Americas. It’s a surprisingly good yarn written deftly by Anders Halvorsen, (Yale, Ph.D Ecology), who has gathered together the milestones, personalities, and the ramifications of wadding an increasingly foreign species into every body of water conceivable.

One simple question sealed the fate of trout fishing the world over…

An eastern fellow steps off the stage in San Francisco, straightens his bowler and says, “where’s the salmon at?” – and via the miracle of a desolate stretch of the McCloud and assisted by the transcontinental railroad, the McCloud River Rainbow became the savior of the east coast and the known world.

… at the expense of everything that was living there already.

It was nip and tuck which would inherit, fish cultivation was in its infancy, with most of the eastern fish hatcheries owned by hobbyists or were for-profit, merely raising the Eastern Brook Trout for later sale at market.

The Good Old Days weren’t … and the East Coast was faced with increased pollution as a result of a burgeoning population. Many of the eastern watersheds died horribly, with the Atlantic Salmon the first to go. In an effort to restore their numbers an embassy was sent to the west coast to bring salmon back to raise and release in eastern rivers.

The McCloud river obliged them and the hatchery created there sent Pacific Salmon eggs packed in moss, whose fry were dutifully released – never to be heard from again. The salmon transplant may have been an abject failure, but the feisty nature of the McCloud River Rainbow was duly noticed.

The author warns us about our continued reliance on the planting of a single species, and how desirable characteristics of the Rainbow, its ability to thrive in warmer water, and willingness to eat artificials, set the stage for massive fisheries collapse when they’re exposed to an invasive or even domestic pest.

Like Whirling Disease – which the Eastern Brook and Brown trout can survive – but decimates the Rainbow trout as it’s especially vulnerable. The narrative of how Colorado infected 13 of its 15 watersheds by accidentally, then intentionally, planting Whirling Disease infected Rainbow trout being moot evidence.

“It was not until 2003, in the face of overwhelming evidence, and after spending well over $10 million to decontaminate only some of its facilities, that Colorado finally stopped stocking fish from hatcheries infected by the M. cerebalis parasite. By that time, though, it was too late. The disease had established itself in the wild, and the department’s policy of stocking diseased fish , Nehring later declared, was the primary cause.”

Whirling disease has been a hot topic of late, troublesome because of the thirty year lifespan of spores in stream sediment, and one of the Big Three invasives that conservation organizations have blamed on us anglers.

Trout planting and quality watershed are synonymous in hatchery circles, and the introduction of invasives as well as hatchery trout have had a profound effect in many states, not just Montana and Colorado. The story of hatchery induced plague is one of many ignored by the conservation literature, as was Colorado’s solution; adopting the “Hofer” strain Rainbow for production, a rainbow trout developed in Germany that is entirely proof against Whirling Disease.

In contrast, Montana fisheries were handled differently. The introduction of rainbows destroyed the indigenous populations of trout, and when Whirling disease followed on the Madison they ceased trout plants entirely, allowing the Brown trout to encroach on the much reduced and ailing population of rainbows, and waiting out the collapse with an eye towards Mother Nature. Which obliged them with a whirling disease resistant strain of Madison River rainbow trout that developed on its own.

… as it had in other states, and with as much mystery.

“But when I asked Vincent what Montana planned to do about the disease and specifically whether there were any plans to introduce resistant fish, as Colorado had done, he demurred. ‘I’m a little reluctant to just start whaling around out there, personally,’ he admitted. “’I’m somewhat leery that it may backfire on us.’ “

It’s as much a tale of the men behind the fish as it is of the fish itself, which allows the book to be part narrative, part science, part history, and an engaging and fun read, especially the sections on WWII bomber pilots and the first attempts at aerial stocking.

But I’ll leave all the really tasty tidbits for you to learn, like how the Rainbow trout is intertwined with the Charge of the Light Brigade and how it was the popular choice to restore America’s flagging manhood.

“Put and Take” still weighs heavy in the mind of Fish and Game officials and most states manage their fisheries to suit the need of the casual angler:

“Take, for example , a sunny Sunday morning in May. Mr. Los Angeles looks out of his window and for no good reason at all discovers that there has been a cloudburst on the desert the night before and there is water in the Los Angeles River. By 9:30 o’clock, 20,000 telephone calls have come to the Fish and Game Commission to come out and plant some fish because there is water in the Los Angeles River. Since we have one of the most efficient departments in the country, by 10 o’clock a truckload has started out. We carry a siren on the trucks, by which , at the end of planting, we let everybody know that the planting has been accomplished. By 11 o’clock the fish are caught out of the stream, and at noon the river has dried up again!”

It marks the current state of fisheries management whose early beginnings were about establishing viable colonies of fish, and have degenerated to emphasize “catchables.”

… and we love ‘em, or so the government thinks.

“Every dollar spent growing and stocking Rainbow trout resulted in thirty-two dollars of economic activity through everything from worm sales to airplane fees.”

Success and failure in fisheries management is tied to many of the unique tenets we’ve always associated with fly fishing. While eager to claim our efforts as a causal agent, many of the unique regulations stem from failures in management, and how we capitalized on some inadvertent or timely trauma. A watershed whose fish collapse due to disease makes a reduced bag limit feasible, and sick fish are undesirable as table fare, and can be caught and released without the drama of declaring a river so by regulation.

I found the book alternately encouraging and fraught with despair. It’s plain we’ve learned nothing in a couple hundred years regarding tinkering with native species and the “put and take” notion of modern fisheries management – but it’s also encouraging that we’ve faced these same problems many times – and despite the state of our modern fisheries and their continued decline, a body of work remains that may assist us in pulling some back from the brink.

Full Disclosure: I purchased this book from Amazon.com for its suggested retail price ($17.16)

Tags: An Entirely Synthetic Fish, rainbow trout, McCloud river rainbow, whirling disease, brown trout, hofer rainbow, Atlantic salmon, McCloud river, pacific salmon, Anders Halvorsen

Here I think I’ve got it bad – a two year ban on salmon fishing and me and my fellows either gashing ourselves over too much water or too little, and now they’ve banned fishing on the Sea of Galilee …

Here I think I’ve got it bad – a two year ban on salmon fishing and me and my fellows either gashing ourselves over too much water or too little, and now they’ve banned fishing on the Sea of Galilee …

The true game-fish, of which the trout and salmon are frequently the types, inhabit the fairest regions of nature’s beautiful domain. They drink only from the purest fountains, and subsist upon the choicest food their pellucid streams supply … [It] is self-evident that no fish which inhabit foul or sluggish waters can be ‘game-fish’.’ It is impossible from the very circumstances of their surroundings and associations. They may flash with tinsel and tawdry attire; they may strike with the brute force of a blacksmith, or exhibit the dexterity of a prize fighter, but their low breeding and vulgar manner of eating, betray their grossness.”

The true game-fish, of which the trout and salmon are frequently the types, inhabit the fairest regions of nature’s beautiful domain. They drink only from the purest fountains, and subsist upon the choicest food their pellucid streams supply … [It] is self-evident that no fish which inhabit foul or sluggish waters can be ‘game-fish’.’ It is impossible from the very circumstances of their surroundings and associations. They may flash with tinsel and tawdry attire; they may strike with the brute force of a blacksmith, or exhibit the dexterity of a prize fighter, but their low breeding and vulgar manner of eating, betray their grossness.” codicil of parchment from a Mexican land grant.

codicil of parchment from a Mexican land grant. I always suspected golfers had an extra chromosome or two – what with their fondness for flashy plaids and saddle shoes, and if you play in Florida that risk goes double …

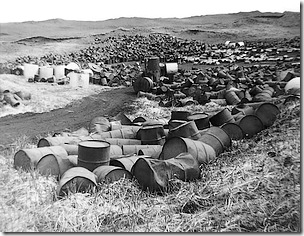

I always suspected golfers had an extra chromosome or two – what with their fondness for flashy plaids and saddle shoes, and if you play in Florida that risk goes double … It started with some small pretense of fairness, Senator Feinstein’s call for a review of the environmental opinion on the Sacramento Delta, an effort to ferret out the “flawed science” that dared put fish before the needs of farms and her pals at the Westland’s Water district.

It started with some small pretense of fairness, Senator Feinstein’s call for a review of the environmental opinion on the Sacramento Delta, an effort to ferret out the “flawed science” that dared put fish before the needs of farms and her pals at the Westland’s Water district. It didn’t work back in the Sixties, when J. Edgar and his G-Men encouraged academics to rename the lowly “Egbert Carp” to “Grass Carp” as it’s known today.

It didn’t work back in the Sixties, when J. Edgar and his G-Men encouraged academics to rename the lowly “Egbert Carp” to “Grass Carp” as it’s known today. After a two year ban on commercial fishing the result is

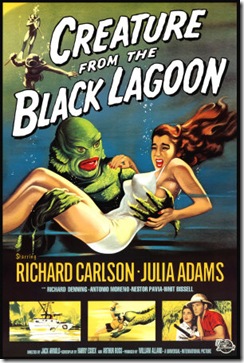

After a two year ban on commercial fishing the result is  Those giddy days of Halloween television, Ma insisted you were too young to watch a pissed humanoid water breather slime its way through the streets preying on the unwary, dragging screaming female teens into the cold bosom of a nearby bay …

Those giddy days of Halloween television, Ma insisted you were too young to watch a pissed humanoid water breather slime its way through the streets preying on the unwary, dragging screaming female teens into the cold bosom of a nearby bay … The ringtone belonged to “Deep Walnut”, the Yolo county landowner I’d turned to the side of righteousness. The pleasantries were brief, and I was informed that the annual “crop report” outlining the sins of watery tomatoes had been secreted on the grounds of my residence.

The ringtone belonged to “Deep Walnut”, the Yolo county landowner I’d turned to the side of righteousness. The pleasantries were brief, and I was informed that the annual “crop report” outlining the sins of watery tomatoes had been secreted on the grounds of my residence.