Many would say that nothing in fly fishing is more addictive, the lure of the surface fly and the visual take. Most would insist that no component of fly tying is more expensive, as the surface fly and accompanying visuals come at a horrific price.

Many would say that nothing in fly fishing is more addictive, the lure of the surface fly and the visual take. Most would insist that no component of fly tying is more expensive, as the surface fly and accompanying visuals come at a horrific price.

A novice stands in front of the abyss, the friends and expertise of the fly tying class a distant memory, the cautionary advice forgotten, and the long wall of genetic hackle menacing, unfamiliar, and incredibly expensive.

Need is well defined; brown and grizzly for the Adams, Humpy, and Western flies, ginger for the light Cahill, and medium dun for the Quill Gordon and most of the east coast. Price precludes grabbing one of everything, and there are a dozen capes labeled #2, each the better part of a hundred dollar bill – whose shade and cut look similar, only which one to buy?

Is someone going to yell if you take one out of the package? Do I really want to learn to tie flies? The book said to press the barbules against my lower lip, the instructor said to buy saddles, and that fellow mentioned Leon’s Coque made the best tails – I don’t seem him anywhere, and the sinister looking fellow at the register doesn’t seem interested …

… I could use some help!

Forums are ablaze with questions about hackle; where is it cheapest, which is the best-est, and how can I get the most-est – interspersed with; which do I want, what should I get first, are saddles just as good, and the ever-present, “… the guy in the book said …”

Like everything else on the Internet, there’s much wheat and even more chaff.

Chicken Necks – Past to Present

Compared to the past there is much less variety on the wall of the local shop. Most fly tiers are introduced to genetic chickens in their first tying lesson, and rarely encounter capes from China and India – which dominated the trade in year’s past.

Most of the non-genetic hackle goes to the costume market, where they’re made into long feather boas in both natural and brightly dyed colors. India capes are about a third the size of our hormone laced genetics, and Chinese capes are typically about 50% larger than India necks, but still markedly smaller than what Whiting packages.

Occasionally you’ll run across some in fly fishing stores, but not often. Instead you’ll find Chinchilla necks, that mimic the color and pattern of Grizzly, but have irregular barring and a hint of brown in the black markings. As large grizzly hackles have many uses including bass and saltwater flies – and are adored by costumers, it’s the most common non-genetic sold.

As well as the Indian or Chinese capes, you can encounter a semi-genetic flavor. Some grower that’s attempting to perfect a strain or color to compete with Whiting, whose flock is not yet into that rarified zone commanding ultra-high dollars. These are often Grizzly also, as dyed Grizzly in any size or length is quite saleable.

Packaged saddle hackle is still dominated by non-genetic chickens, in large part because eating chickens are raised by the millions and all are white, or off-white, much easier to dye than naturally colored chickens from off shore. Most are hens, but white roosters still abound in great numbers. Genetic roosters must be fed and pampered for two or more years to yield those foot-long saddles, our domestic rooster is likely to live about half as long before it becomes a MSM chicken.

“MSM” is “mechanically separated meat” – which is a process that yanks non-prime elements like lips, snouts, and pucker off the bone once it’s been boiled into softness. It’s commonly known as a Chicken McNugget, or Hot Dog.

Many shades of Awesome

Today’s tiers still insist on the finest, cheapest, and best – but they’re picking between “great” and “fantastic” in comparison with the past. Dry flies always required two (or more) hackles in the 80’s, and a typical size #16 was about 1.5” long.

Today’s tiers still insist on the finest, cheapest, and best – but they’re picking between “great” and “fantastic” in comparison with the past. Dry flies always required two (or more) hackles in the 80’s, and a typical size #16 was about 1.5” long.

If you were lucky there was a couple dozen in the inch wide nape of India cape, unlucky and you tied mostly #12’s and above.

The worst of todays genetics would have driven tiers into paroxysm’s of joy. It would of been something to stroke or trot out to the amazement of the rest of the crowd, left pristine or given a female name and worshiped.

Those vendors that grade necks – and mention their methodology – use feather count to determine #1’s, #2’s, and #3’s. More feathers per inch yielding more flies tied, and increased value to both breeder and fly tyer. The grade given by the breeder can be ignored. Simple feather count may be useful to differentiate one chicken from another, but it’s not an adequate measure of value to the fly tyer.

Fly tier’s are unique. Each is a different mix of favorite flies, favorite fish, number tied per year, and most common size fished. While feather count has some meaning, so does cut of the neck, color of the cape, and shape and size of the feathers too large for dry flies.

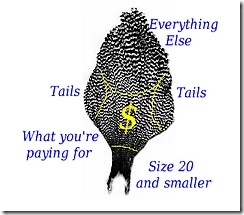

Cut of the Neck: An improper cut usually comes at the expense of the tailing material. Tails are from the right and left edge of the neck’s shoulder, markedly darker and stiffer than the rest of the cape, shaped like a “spade” versus long and skinny, and can be too few to tail all the dry flies the hackle can produce.

Color of the Cape: Color is responsible for probably half of the purchases, especially if the color is uncommon or rare. Color would also describe other visual features such as dark barring, light barring, or black tipped – such as Badger and Furnace necks. Dun necks are particularly valuable in different shades, and is often purchased for the color alone.

Shape and Size of the Feather: Genetic necks make poor hackle tip wings, largely because of the narrowness of the feather. At the tip a slim feather can be quite small and the effect lost amid a thickly hackled fly, especially on Western flies which use much more hackle than their Eastern counterparts. Some genetics can offer a wider large feather which may be suitable for hackle tip wings, and this quality weighed in the purchase decision.

Feather Count: It matters certainly, but is best used to select a candidate tuned to your fishing, not the single criteria that drives purchase. (I’ll have more on the subject below)

How to select the best Neck

Most fly fishermen tie many more flies than the traditional dry, and often fish for other species in addition to trout. It should be no surprise that there are many great necks offered on the rack, but the best neck may have qualities unique to the tyer, with “best” differing from one angler to the next.

Most fly fishermen tie many more flies than the traditional dry, and often fish for other species in addition to trout. It should be no surprise that there are many great necks offered on the rack, but the best neck may have qualities unique to the tyer, with “best” differing from one angler to the next.

The dry fly capable hackle may only be spread over 30% of the genetic cape, why not consider the other 70% as part of an overall grade?

If the tier has a split season, or fishes for multiple species, the shape of the large feathers may dictate his steelhead hackle, bass poppers, or his large saltwater flies. Some necks may be suited for tying these flies more so than others, based on long narrow feathers, or extra wide webby hackles, or just wide blunt tips for wings. A fly tyer conscious of his planned double-use may find the best neck is a combination of his dry fly needs, coupled with his other interests.

… and the grading system used to price the necks, has less value when averaging all the requirements.

You have to remove the neck from the packaging to examine it closely. There should be no objection from the shop staff, but you’ll have to be considerate and not mangle the cape in the process. Both necks and saddles are often stapled to cardboard backing. Flexing the cape a lot will start pulling at the staples – and may even add a bend into both feathers and backing. Your proprietor will not mind a casual exam, but would prefer your hammy-handed tendencies not mar the package permanently.

Each fisherman has a “most common dry fly size” that he uses, and an examination of his fly box will reveal what size that is – this will be our examination criteria for neck selection.

Find the most common size used : Flex the neck just enough so that the feathers lift off those behind, and find the horizontal line on the neck containing your unique “most tied” size. A great neck will have that area in the widest part of the cape, not down low on the narrow isthmus area. Wide equals more feathers, and ensures your most common flies fished match the neck you’re purchasing. It’s very simple, as higher up the cape means better in every cases.

Examine the tailing area : Now examine the shoulders of the cape to ensure the cut has preserved both areas of darker tailing material – and the two regions appear as mirrors of one another.

Examine the larger feathers for optimal uses : Take a look at the shape and size of the larger feathers at the top of the cape. Ensure they match any other use you’ve planned. For hackle tip wings you want broad rounded points, for steelhead hackles you’ll want nice dark barring and the appropriate sizes present, bass poppers should have nice wide feathers to assist in moving water, and saltwater or Pike – perhaps length is the only criteria.

Ensure the color extends to the webby area : On those necks where color is a primary requirement, ensure the desired color extends down through the area you’ll peel off and discard. Avoid those whose color at the tips is perfect – but the color doesn’t extend far enough down the feather.

If you’ve satisfied the criteria above and selected the neck that’s the best fit for all, you’ve got a great neck. Now look at the price, as vendor grade and price is the least important of all.

If it boils down to a #3 and a #1 that are the final two, buying the #3 will the better choice … “a good deal” being the last check on our requirements.

The Neck versus Saddle debate is Over

Necks are no longer as compelling as a quality saddle patch. If you’ve marveled over a 12” #16 hackle you’ll understand what I mean. Necks have been considerably refined from the days of the India cape, but saddles have come even further, to the point where #16 hackles can be a foot long – or even longer.

Necks are no longer as compelling as a quality saddle patch. If you’ve marveled over a 12” #16 hackle you’ll understand what I mean. Necks have been considerably refined from the days of the India cape, but saddles have come even further, to the point where #16 hackles can be a foot long – or even longer.

A quality neck may feature 30 or more hackles that match a single size, perhaps another 15-20 that are a bit too long, or a bit too short. Assuming you get about 50 feathers suitable for a #14, and it’s often one feather per dry fly, the neck has exhausted the supply after four dozen flies.

Take a similar quality saddle with hackles 10-11 inches long, and you can get 3-4 traditional dries with a single feather. If a saddle has more than a dozen such feathers you’ve equaled the capacity of the more expensive neck, and whatever remains is why saddles are a better deal than necks.

I’d suggest that a quality saddle can produce 15-20 dozen flies in the same size versus 4 dozen for the cape.

I converted to saddles some three years ago, the down side being there’s no tool or container on the bench to hold scraps of hackle that’s seven inches long …

But nothing is the Perfect Feather

Saddles offer greater value, but there are pros and cons with both necks and saddles, and it’s important to understand all the issues.

Necks:

Stiffer stems, greater variety of sizes, tailing material present, wider feathers, blunter tips, hackle under size #18 available.

Saddles:

Flexible stems, fewer sizes, longer length, no tailing material present, narrower feathers, needle tips, no hackle under #18 available.

Each of the attributes mentioned above has a corollary in tying that will either be hindered or assisted. Probably the most important difference between necks and saddles is that no tailing material exists on saddles where it is plentiful on necks. Perhaps the fibers on the largest saddles can be long enough for tails, but they are not the hard, shiny, fibers present on the shoulder of a chicken neck – they are much softer by comparison.

Having dozens of left over capes lying around, most of which are missing the small trout hackle, means that I can find tails on older necks and use the saddle only for the hackle that supports the fly.

In summary, a tyer needs both – but necks are likely to be upstaged by saddles via cost and additional capacity.

While genetic feathers show no signs of relinquishing their grip on the hackle market, there is still plenty of uses for a non genetic neck or saddle, only they’re becoming increasingly hard to find. Both hackle tip wings (Grizzly) and large well marked feathers are still in great demand on many styles of fly, and while we get increasingly spoiled with better and longer hackles, we’ll still need plenty of the regular feathers to handle the ignoble tasks other than holding up a dry fly.

Excellent as usual, thank you.

I too prefer saddles, but then I have a lot of old necks lying around. And oddly enough, my head is attached to an old neck.

Though I have plastic contaienrs full of more than my fair share of genetic necks from multiple suppliers, I still find that I reach for a good fly floatant. A good fly floatant will float a soft hackle. Longer than you would expect, too. I do believe that genetic hackle for dries is another great fly fishing marketing ruse. Admittedly, I am addicted to looking for and then hoarding the ‘perfect’ color. Do the fish care? The hackle grower does.

Good stuff, Keith.

Yet another super informative and entertaining article which is much appreciated! Also, just got my 2010 Hatches magazine and really enjoyed your article on dubbing. Thanks & keep up the good work!!