Per request I’ll continue to post additional fly beautification tips in a weekly format. These will comprise hardscrabble lessons learned somewhere after beginner and before complete mastery.

Most tiers that tiptoe around the craft use their fishing instincts when no instructor or book is available. Most of us started as dry fly fishermen and it’s not surprising that most new fly tiers attempt the dry fly more often than nymphs.

… which is too bad. Tying nymphs is far more forgiving than the delicate and strictly proportioned Catskill dry. A novice tier can hold up some lumpy looking stonefly and if critiqued can respond with “ … well, all the stoneflies in _____ Creek are fat.”

… and if I had been the unfortunate to task the fellow – I’d blush like hell and backpedal in a hurry – never having fished over “fatty” Plecoptera …

The Catskill dry is completely unforgiving. It’s territory and techniques have been practiced for more than a hundred years – and artistic license must be defended, even for expert tiers.

One of those oft-mentioned-quickly-forgotten principles is made more difficult in the presence of the Perfect Feather …

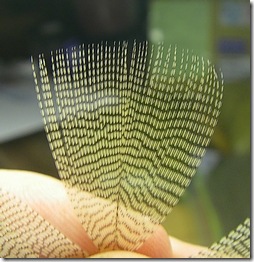

Above are two examples of the Perfect Feather; a foot long #16 grizzly saddle hackle, and a well marked (lefty) Wood duck flank feather with perfect tips. Both are treated with awe by the owning fly tier – and both can cause your fly to suffer cruelly if you’re not diligent…

You’re a kid in a candy store, all those precious tips are in a straight line and unbroken. Giddy, you fail to clip the center stem because it’s perfect too.

You forgot that all feathers are either a left or a right, even foot long saddles and untouched Wood duck flank.

The wood duck will be your undoing twice. In the first case the stem will cock one wing to the left, and in the second, the stem center will retain 9 or 10 fibers attached and you’ll have to compensate by yanking fibers from the far wing to the near side to equalize that natural bulk.

The picture at right shows the Perfect feather now clumped together with the center stem included. Note how all’s well – there’s no clue that anything is other than perfectly straight.

You’re thinking of dumping all your “lemon-dyed mallard” – as the sight of the wood duck with its pristine coloration, fine markings, and perfect tips – make it so much more pleasurable to work with – even justifying the hideous cost to lay in a goodly supply.

Unfortunately like Ulysses and the Sirens – their song is so beautiful, you’re ignoring the approaching rocks …

Now you can see why you remove the center stem. The left side is thin and has a different angle than the right wing.

The cause is simple. You had to pull the loose fibers over to the right side to balance the two clumps – leaving the left, just the stem section. It’s thin because the fibers are attached to the center spine and have no “give” to move around.

We were lured onto those rocks consciously …

The picture at right shows the same wing as before. I’ve removed the wing from the shank, clipped out the center stem and retied it back on.

Note the difference with the picture above. the left wing is relaxed, the right wing is less dense and tighter – as you didn’t have to pull everything to that side to compensate for the stem on the left.

That foot-long Grizzly saddle is just as bad. You’re used to applying six or eight turns of hackle to your dry flies, but the lure of virtually unlimited hackle means you add four or five extra wraps and crowd the head. Crowding means fibers trapped in the knot that’ll wick the head cement right into the eye.

It’s the lure of the Perfect Feather. You won’t find it mentioned in any tome or DVD, and only your steely resolve to overcome it’s sweet song …

Tags: wood duck flank, grizzly saddle, upright and divided wing, center stem, lure of the Perfect Feather, steely resolve, fly tying

When you tie a cahill with wood duck, do you use an entire feather per fly? I suppose you could use the rest of the barbs for birds nests or the like… But still, at $0.75/feather, that makes for some spendy cahills!

Spencer,

There are many ways to wing the Light Cahill (or any catskill dry using similar wings)- but I’d suggest the two most common are the a)entire feather, and b)part of the feather.

As a Western tyer – I use more hackle and more wing material than many of my eastern counterparts. The historical justification has been elevation and faster water – requiring a bit more visibility, and additional hackle to maintain bouyancy.

… and the “tip” of the post was to remember to clip the center stem – which influenced my choice completely.

Wood Duck has these beautifully shaped feathers commonplace, especially compared to the bedraggled package of lemon-dyed mallard.

Mallard has many larger flank feathers that allows you to use the sides of the feather rather than the tip – sometimes winging two or three flies from a single feather.